Recreated Leipzig Liturgy Follows Old Bach’s Handwritten Notes

For twenty years, Warren Stewart and Magnificat have been pioneers in performing the great sacred works of the 17th century in their full musical-liturgical context. Whether they are doing Charpentier’s Midnight Mass or Monteverdi’s Vespers, situating these great works in a more complex setting brings their color and polyphonic richness into sharper focus as they blossom into relief on a sonic backdrop that creates its own dramatic arch. Musical services for the Christmas holidays during the baroque era often were as lavish and joyous as they are today, and Magnificat’s recreation of these services has become something of a collaborative tradition with SFEMS in recent years. This year, Magnificat will move the clock forward to the first Sunday of Advent in the year 1735, to recreate a Lutheran service at St. Thomas of Leipzig. Concerts take place the weekend of December 11–13, with performances in Palo Alto, Berkeley, and San Francisco.

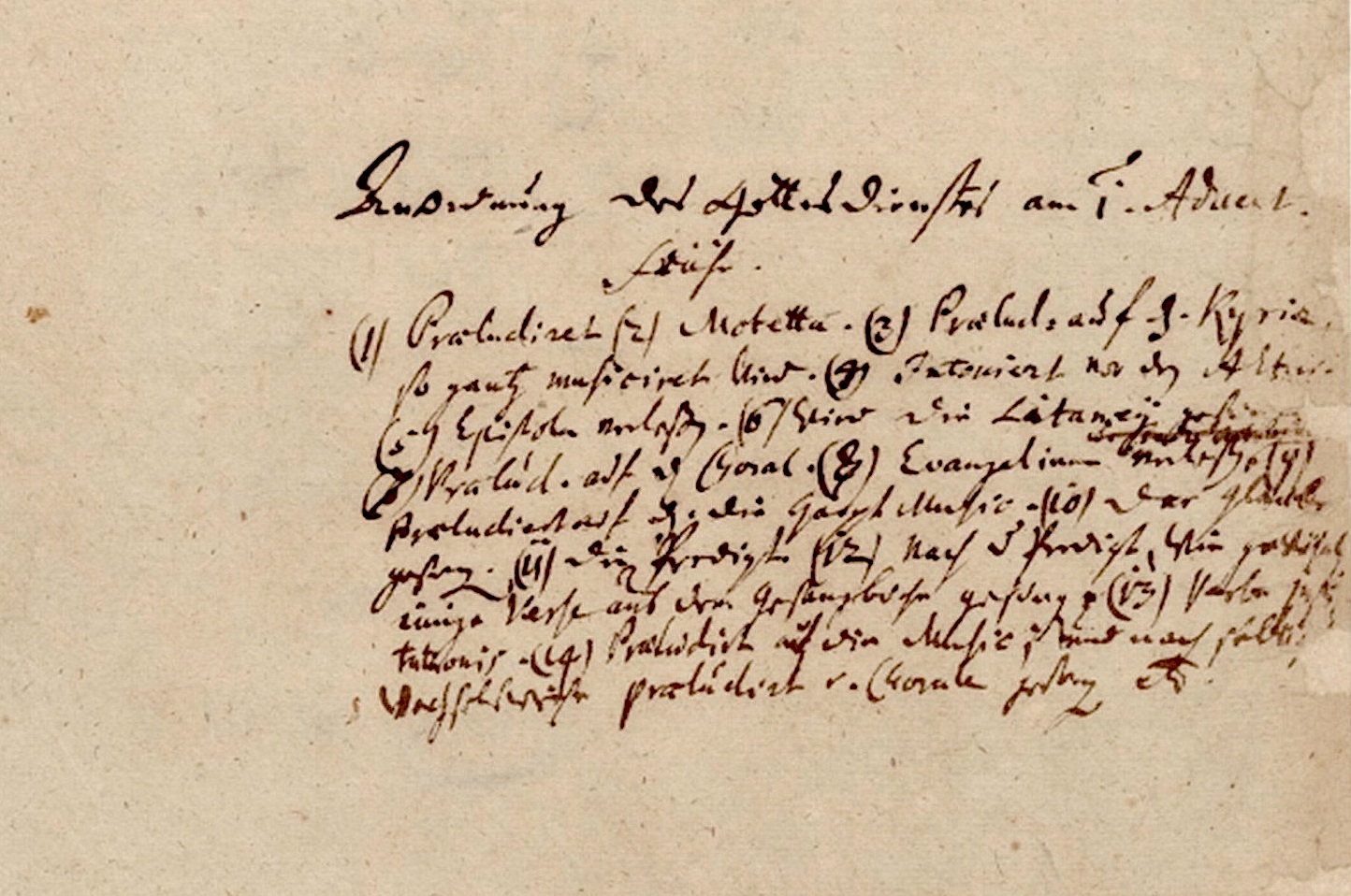

This will be a sparkling event, with one-to-a-part singing that will bring Bach’s joyous and intricate music into crystal clear focus. The musical riches of this concert—which is based on Kapellmeister J.S. Bach’s handwritten notes for the service—will include both Bach’s Cantata BWV 36, Schwingt freudig euch empor, and his Mass in G minor; as well as other, separate mass movements, motets, and instrumental works by Bach, Dieterich Buxtehude, Andreas Hammerschmidt, and J.H. Schein; plus liturgical chant and chorales. In keeping with the historical practice of Bach’s day, the audience will join with choir and orchestra in singing the chorales.

Magnificat’s Artistic Director, Warren Stewart, offers the following notes on the Leipzig’s liturgy and musical practice and on Bach’s role as Kapellmeister in creating and directing this service.

* * * * *

Since the nineteenth-century revival of the music of Johann Sebastian Bach, we have become accustomed to hearing the composer’s sacred music performed as autonomous works in concert halls. However, Bach never envisioned such a performance of his cantatas, Passions, and oratorios. As musicologist Robert Marshall has noted, “such compositions were not intended for the ‘delectation’ of a concert public, but rather for the ‘edification’ of a church congregation … Bach’s cantatas, in fact, were conceived and should be regarded not as concert pieces at all but as musical sermons; and they were incorporated as such in the regular Sunday church services.” Magnificat’s program is an attempt to re-create the experience of a Leipzig church-goer who had the unimaginable good fortune each week to be able to hear music written and directed by Johann Sebastian Bach. In undertaking such musical make-believe, we have the chance to experience the theological and textual unity, the heterogeneity of musical styles, and perhaps even some of the spiritual intensity that Bach and his contemporaries may have felt during Hauptgottesdienst on the First Sunday of Advent.

In reconstructing the liturgical context for Bach’s sacred music, the first source is Martin Luther himself, who, during the early years of the Reformation, established the pattern of worship for the Lutheran Church in two documents: the Formula missae et communionis pro Ecclesias Vuittemburgensi (1523) and the Deutsche Messe und Ordnung Gottesdienstes (1526). While Luther retained the basic structure of the medieval Latin Mass, he drastically reinterpreted the Canon of the Mass, taking what had been a largely inaudible series of prayers and reducing them to the Words of Institution, which were sung aloud to the congregation by the celebrant.

A most significant change in the celebration of the Mass was the incorporation of congregational singing, with Luther himself adapting many popular melodies and plainchant hymns into chorales for corporate singing. The principal points in the liturgy for congregational singing were between the Epistle and Gospel readings, replacing the Gradual (hence Gradual-Lied), and during the taking of communion. Typically, the congregation would sing the melody in octaves, with or without organ accompaniment in alternation with the choir, who sang homophonic harmonized settings.

While Luther’s Mass served as the starting point for liturgy in the reformed church, there was considerable diversity in detail from city to city with each community adapting local tradition to the new confession. In the thirty years following the publication of Luther’s Formula Missae, as many as 150 different Lutheran church orders were issued.

The liturgy in Bach’s Leipzig had its origins in a document entitled Agenda das ist Kirchenordnung für die diener der Kirchen in Herzog Heinrich zu Sachsen fürstenthum gestellet (Leipzig, 1540). This church order was reprinted several times over the years including an edition published in 1712 that included the chant for the clergy. The other principal source for the servce music on the program is the Neu Leipziger Gesangbuch, published by Vopelius in 1682, which contains hymns and liturgical chant for the choir. This hymnal was based on the Cantional, composed by Johann Hermann Schein in 1630 and, as a result, all of the harmonizations that we will be singing are by Schein.

Bach himself provides some interesting insight into the liturgy in the scores to two Advent cantatas setting the chorale text Nun komm der Heiden Heiland, BWV 61 and BWV 62. Perhaps because the cantatas were written for the first Sunday of the church year, or because he was new to the peculiarities of the Leipzig litugy, Bach sketched out the items of the liturgy (see at right), including point at which to organ would provide introductory preludes, information normally not included in formal sources.

A non-liturgical, but essential element of the experience of a Leipzig church-goer was, of course, the organ. It is somewhat disappointing to learn that Bach rarely played the organ during services, occupied as he was with the directing of the music from the harpsichord. There were numerous points in the liturgy in which the organ would have been played, most often by one of Bach’s assistants, as a prelude and postlude, and to introduce the chorales and cantatas.

Thus, in reconstructing Bach’s liturgy we have a fascinating collage of musical styles: Medieval plainchant, Reformation folk-song based chorales, seventeenth-century motets and chorale harmonizations, and, of course, Bach’s marvelous cantatas, themselves extraordinarily polyglot stylistically. Such was the musical experience of a church-goer in Leipzig during Bach’s tenure as Cantor.

The Sunday service began in Leipzig at 7:00 a.m. with a hymn sung by the choir followed by an organ prelude and the Introit motet. These motets were often drawn from collections of motets like Florilegium portense, published in 1621 or from similar volumes contained in the library at St. Thomas. We will perform the Advent motet Machet die Tore weit composed by Andreas Hammerschmidt, organist at Zittau and one of the most popular composers of sacred music in the mid-17th century. Still a staple of Advent and Christmas celebrations in Germany, the closing verse of Hammerschmidt’s motet sets text from Matthew’s Gospel proper for the First Sunday of Advent, “Hosianna dem Sohne Davids.”

The organ then played a brief prelude before the Kyrie and Gloria. Bach’s Mass in G minor (BWV 235), like his other Missae Brevi, has suffered from misguided notions of originality since it is a “parody” work, in that Bach set the text of the Kyrie and Gloria to previously composed music. Although Bach assembled at least five such settings between 1735 and 1748, we have no specific reference to their performance nor the motivation for their composition. Most likely the individual movements were chosen for their intrinsic musical value. Perhaps Bach’s concentration on music for the ordinary during the last years of his life reflected the concerns of the Leipzig clergy. In a way these pieces are more like “Greatest Hits” collections, for indeed, Bach seems to have rescued some of his finest arias and choruses from cantatas that could only be used on specific Sundays and recast them in a setting of the ordinary that could be used on any major feast day.

The Mass in G minor, written most likely in the late 1730s, is perhaps the most musically unified of his ‘parody masses’ with the final four of its six movement drawn from a cantata, Es wartet alles auf dich (BWV 187), first performed in August 1726. The opening chorus of the Mass appear originally in the cantata Herr, deine Augen sehen nach dem Glauben (BWV 102) also first performed in August 1726, while the Gloria chorus uses music from the opening chorus of the cantata Alles nur nach Gottes Willen (BWV 72), also coincidentally first performed in 1726.

After the collect and the reading of the Epistle, the congregation sang the Gradual-Lied, in this the case Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland, in alternation with the choir, after which the gospel of the day was read. It was after the reading of the Gospel that the Hauptmusik, in the form of a cantata based on the gospel text was performed. The Hauptmusik for our Advent Mass is Schwingt freudig euch empor (BWV 36). The non-chorale-based movements of the cantatas have their origins in a secular cantata written for a Leipzig University professor in 1725 and adapted the following year as a congratulatory cantata for Countess Charlotte Frederike Wilhelmine of Anhalt-Cöthen. In 1731, Bach re-worked the music as a cantata for the first Sunday of Advent by adding three stanzas of the Advent chorale Nun komm der Heiden Heiland, and the final stanza of the chorale Wie schön leuchtet der Morgenstern. The unusual structure is unique among Bach’s cantatas and firmly roots the work in the Advent liturgy. Like many of Bach’s cantatas, BWV 36 is divided in two parts, the first to be performed as the Hauptmusik after the Gospel and the second to be heard toward the end of the Mass during communion.

Following the performance of the Hauptmusik, the congregation joined in the singing of the creedal hymn Wir glaüben all in einen Gott, though in some services the Credo was sung in Latin by the choir. In our program, the first verse will be sung in unison, the second verse will be a fantasia on the chorale tune by Bach (BWV 1098) and the third verse will be in Schein’s harmonization found in the Leipzig hymnal. After the singing of the creed, about an hour into the service, the focal point was reached with the preaching of the sermon. Often more than an hour in length, the sermon (omitted from our program) was typically an elaborate analysis and explication of the Gospel of the day and often served to proclaim or reinforce the political and ideological agenda of the clergy.

At principal celebrations like Easter the Latin preface was intoned after the sermon, with choral responses provided in the hymnal, which lead directly into the Latin Sanctus (without the Benedictus or Osanna), sung in simple monody, in one of the hymnal’s polyphonic settings, or in a concerted setting. Bach wrote at least six different concerted settings of the Sanctus during his tenure in Leipzig, three by other composers and three of his own composition. We will perform the Sanctus in G major (BWV 240), which is most likely not written by Bach, though scholars have been unable to identify the composer and it remains among Bach’s cataloged works. Following the Verba institutionis, or Words of Institution, and during the taking of communion another cantata, or as in our program, the second half of a two part cantata was heard, followed by prayers and a benediction.

SFEMS presents Magnificat at 8:00 p.m., Friday, December 11, at First Presbyterian Church, 1140 Cowper Street at Lincoln, Palo Alto; 7:30 p.m., Saturday, December 12, at First Congregational Church, Dana and Durant Streets in Berkeley; and 4:00 p.m., Sunday, December 13, at St. Mark’s Lutheran Church, 1111 O’Farrell Street at Gough, San Francisco.

Tickets are available online or through the SFEMS box office at 510-528-1725.