by Sheli Nan

There is a structural integrity to rhythm. By that I mean rhythm is integral to who we are as human beings; it arises both consciously and unconsciously by the ways we use our bodies. We tie our shoes, for instance, in a learned rhythm. Although we are taught the steps to complete this task, each of us does it in our own time and in our own way. The manner and speed in which we walk, talk, and gesture are unlearned rhythms. We do these actions so much and so naturally that we do not think of them as rhythmic experiences. However, as we become more aware of them, this very fact teaches us to identify and utilize the rhythmic properties of our lives.

The fact that there are rhythms which are found in widely dispersed cultures supports the idea of the origin of musical rhythm originating from the information our bodies have given us. There are certain rhythms that human beings seem to get intuitively, wherever they come from. Obviously, the time signature of 4/4 is a perfect example of common time. Whether it’s the fact that we have two arms and two legs, or two eyes and two ears, or that we divide our money into 4, etc., we are comfortable with this rhythm, and it shows up again and again in all we do.

As with rhythm, there is a structural integrity to harmony. When considering a piece of music these elements of composition can be structured or unstructured, in sync or not, yet they must retain this basic integrity in order for the piece to be “successful.” There must be an underlying sense of unity creating an experience of plasticity, which governs and fills the spaces around and between the written notes.

As a living composer, I am conversant and comfortable with 21st-century harmony. My personal language is created by a nod to the past, a well-integrated knowledge of the present, and a plea for the future. What is this plea? It is that there are many voices, experiences, and paths to understanding our multi-dimensional selves. When I think of potent rhythms that inspire, that resonate deep within me—for instance the Alberti bass line, the fandango, the I IV V progression—I know that they inspire and resonate with others, and for this reason, we can find examples from all over the globe that we can relate to or in fact mirror something we may have composed.

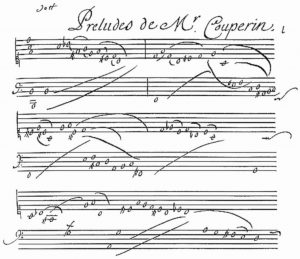

Consider how this tension between the universal and our individual experience and practice is played out in the unmeasured prelude. These preludes were composed during the baroque period, especially by the French but by others as well. Louis Couperin and his nephew François were recognized masters of the form. The unmeasured prelude has no time signature, no key signature, and no bar-lines. Accidentals are incidental to the note and not repeated unless notated once again. And here is where structural harmony comes in—leading the individual player to interact and interpret the lines of notes to make sense of them. Frequently no two people will play the prelude in the same way. We use all our faculties and all of our training and understanding of historical practice to “crack” the imagination of the composer we are performing. We also take into account the quality of the instrument on which the prelude will be played—including the country where it was built and the historical model on which it is based—and how it affects the composition, touch, timbre, and sound.

There have been few if any unmeasured preludes composed in the present day. I offer all of you a piece of mine, an unmeasured prelude I wrote on commission from harpsichordist Arthur Haas (published by PRB), and I ask you to play it, enjoy it, and see if you can find both the rhythm and harmonic substance and structure of the piece in this 21st century. I have to some extent specified the note values, and this can be used in interpreting the piece (many of Louis Couperin’s preludes have only whole notes). I am fascinated by this form and the challenges it presents. I believe the organic foundation for an understanding of rhythm and harmony can be intuited by feeling and listening closely. Please send me your interpretation of this piece. Let´s see how many harpsichordists interpret this similarly or differently.

Sheli Nan is a Bay Area harpsichordist, keyboardist, teacher, composer, and author.