SFEMS’s regular concert season concludes the weekend of March 14–16 with the concert series debut of the Farallon Quartet, Annette Bauer, Letitia Berlin, Frances Blaker, and Louise Carslake, recorders. Recognized for their sensuous blend and warm tone, Farallon is acknowledged to be one of the finest professional recorder ensembles in the United States today. Early Music America compares their sonority to “the sound one would get if one could turn honey into wood or stand underneath a caramel fountain.”

Farallon’s virtuose, playing a veritable arsenal of flutes 6 inches to 6 feet long, will be joined by soprano Jennifer Paulino and lutenist John Lenti for “Amaryllis,” a concert of love songs and consorts from Renaissance Europe’s courts and countryside. The program will range from John Dowland’s tender ayres to lively Spanish villancicos and Italian frottole to the sublime perfection of Josquin’s polyphony to popular songs and dances of the age and the highly ornate art music composers built around it. The rich texture and sprightly flexibility of the recorder consort create the perfect vehicle to showcase this music of panache, wit, and charm. Farallon’s Louise Carslake offers this historical preface to their performances.

Love Songs and Consorts from Renaissance Europe

by Louise Carslake

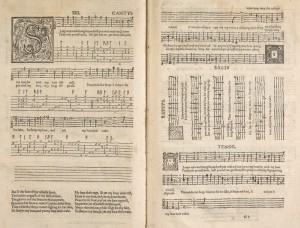

In the 16th century there was a tremendous increase in the amount of music that was written specifically for instrumental performance. This was reflected in the parallel development of instrumental consorts of recorders, flutes, reeds, brass, violins and viols. In addition to this repertory of dances, ricercars, fantasies, and the like, it is well established that all vocal music was in fact fair game for instrumentalists, and even settings of the Mass have survived in transcriptions for instruments. The link between vocal and instrumental music can further be seen in the way the consorts of instruments were constructed to match the soprano, alto, tenor, and bass ranges of the human voice. By the late 16th century it is common to find music published as “apt for voices or instruments.” Farallon’s program features a wide variety of Renaissance music from across Europe that explores the possibilities for recorder consort, lute, and voice.

John Dowland’s famous lute songs were printed in such a way that they could be sung by a solo voice with a written-out polyphonic lute accompaniment, or as four or five-part consort ayres. The opening piece in our program “Can she excuse my wrongs” was also published as a purely instrumental galliard in his Lachrimae collection. All three of these approaches to Dowland’s elegant compositions can be heard on Farallon’s program.

Josquin des Prez ‘s chansons “Incessament livré” and “Nymphes, Nappes” are suffused with the melancholy that was so fashionable at the time. In its original form, “Nymphes, Nappes” (Nymphs, veiled, sea-dryads, dryads, come and weep at my misery) is for six voices, and it is notable that Josquin used a plainsong cantus firmus in the two tenor voices in this secular song. The version for solo lute on our program was intabulated by Simon Gintzler in 1547. “Fault d’argent” is based on what appears to be a pre-existent folk melody, which is set in canon between the second and fourth parts. This is a perfect example of Josquin’s ability to hide the strict form of canon in a delightfully imitative 5-part chanson. Josquin’s Missa Pange Lingua is a paraphrase Mass in which a plainsong hymn melody (“Sing my tongue”) forms the basis for every melodic motive, but without being quoted exactly.

Jacques Arcadelt’s touching four-part madrigal “O Felice Occhi Miei” was adopted by Diego Ortiz in his treatise of 1553 to demonstrate the skill of composing divisions on a pre-existing polyphonic piece. Here we present the original madrigal in a version for voice and lute, followed by the same piece with the cantus and the bassus lines as ornamented by Ortiz. We finish this set with Farallon’s arrangement of Ortiz’s instrumental setting of a passamezzo moderno bass line with melodic variations above.

The frottola is a secular genre that is closely associated with the courts of Ferrara and Mantua in late 15th- and early 16th-century Italy. Ottaviano Petrucci published eleven volumes of these popular pieces between 1504 and 1514, with much of the music probably originating at the court of Isabella D’Este. As a young girl living in Ferrara, Isabella D’Este studied music with Johannes Martini, and, after her marriage to Francesco Gonzaga, she moved to Mantua where she employed both Marchetto Cara and Bartolomeo Tromboncino. Isabella was a skilled musician who sang and accompanied herself on the lute, and supported the kinds of music that she herself could perform. Her personal musical interests and her taste in poetry clearly shaped the music composed and performed for her, and thus the history of Italian secular music. The style of the frottola is very different from that of the Franco-Netherlandish imitative song in its chordal orientation and its use of text-derived rhythmic patterns. The frottola text is usually set syllabically and only the highest part has words and a true melodic contour. The bass line provides the harmonic structure and the inner parts fill out the texture with contrapuntal work, which explains why frottole are so appropriate for performance by a solo voice with instrumental accompaniment. Many frottole were arranged and published for voice and lute by the lutenist Franciscus Bossinensis. John Lenti will play Bossinensis’s intabulation of Tromboncino’s “Zephyro spira.”

The overwhelming majority of songs in the early Spanish cancioneros (song books) are villancicos, a form rather similar to the Italian frotolla. Juan Vásquez published his collection of Villancicos y cancioneres for three, four or five voices in 1551. “De los álamos vengo, madre” one of his best known villancicos, is unusual in that the simple, folksong-like melody is in the third voice rather than the highest. The great Francisco Guerrero is primarily known for his church music, but he also wrote several secular villancicos early in his career. He later insisted that these texts be “spiritualized” before he would allow them to be published, and when “Dejo la venda” appeared in 1589 it had the sacred text “Dejo el mundo.”

When English poet Richard Edwards published a collection of courtly verse in 1576 under the title The Paradise of Dainty Devices, he advertised the poems as being “aptly made to be set to any song in 5 parts or sung to instruments.” The consort song to which he was referring, for voice and instrumental quartet (probably viols, but quite suitable for recorders) became a characteristic English song genre that reached its zenith in the consort songs of William Byrd. The two consort songs by Byrd on this program, “Lullaby my sweet little baby” and “Though Amaryllis Dance in Green” were published in his Psalms Sonnets and Songs in 1588. In the beautiful “Lullaby my sweet little baby” Byrd has indicated that the Medius, or second voice is “the first singing part.” This consort song became so popular that the whole collection became known as “Byrd’s Lullabys.”

Two of the pieces on this program are sets of variations originally written for the keyboard. Antonio de Cabezón’s “Diferéncias sobre el canto del cavallero” is based on a Spanish folksong, the cavallero (knight’s song); and Sweelinck’s “Onder een linde groen” (Under the green linden tree) is based on a Dutch song of the same name. We have divided the elaborate variations in both pieces between the four recorders. William Byrd’s “Pavan and Galliard” are adapted from keyboard settings in the British Library. The repeats of each section include written-out variations for the keyboard, to which we have added our own variations more suited to recorders.

Friday, March 14

8PM

First Lutheran Church

600 Homer at Webster, Palo Alto.

Saturday, March 15

7:30PM

St. John’s Presbyterian Church

2727 College Ave. (at Garber), Berkeley.

Sunday, March 16

4PM

St. Mark’s Lutheran Church

1111 O’Farrell St., San Francisco.