by Debra Nagy

The SFEMS concert season continues the weekend of March 2 with three performances by Ohio-based Les Délices (Debra Nagy, baroque oboe; Julie Andrijeski and Adriane Post, violins; Emily Walhout, viola da gamba; and Mark Edwards, harpsichord), whose program will present some of the daring, experimental works from the French Rococo, works full of wit and elegance by François-André Philidor, Jean-Philippe Rameau, and others.

Entitled “Age of Indulgence,” Les Délices’ program spotlights the musical culture of Paris in the 1740s and ‘50s, a world with a wealth of opportunities to find a patron and thrive as a musician. “The works on our program don’t conform to popular expectations about Baroque music, but they’re not quite Classical either,” writes Nagy in her program note, below. “Rather, they mix the humor and wit of early Haydn and Gluck with some of C.P.E. Bach’s sturm und drang, adding characteristically lush French harmonies to create a truly unique sound. The result is a fusion of baroque gestures and Classical forms that combine with harmonic and technical virtuosity to yield expressive extremes.”

Founded by Nagy in 2009, Les Délices has established its reputation for “concerts and recordings…that are journeys of discovery” (The New York Times). The group’s debut CD was named one of the “Top Ten Early Music Discoveries of 2009” (NPR’s Harmonia), and their performances have been called “a beguiling experience” (Cleveland Plain Dealer), “astonishing” (Cleveland Classical), and “first class” (EMAg: The Magazine of Early Music America).

Debra Nagy discusses the decadently daring delights on their program.

With enormous wealth at their disposal and wielding significant political power, French aristocrats could pursue leisure as an occupation or lose themselves in romantic intrigues. They could decorate extravagant houses with the help of professional house painters in their area, so they have the chance to be able to follow the latest trends in art, architecture, and interior design or establish their reputations as patrons of the arts. In fact, a very small percentage of the population in France controlled 90% of the wealth, and the 1750s saw multiple attempts at tax reform defeated. That said, native and foreign musicians found opportunities to thrive in the fashionable French metropolis, establishing rich and varied careers that included performing in patrons’ house orchestras, playing chamber music in exclusive salons, teaching wealthy, influential students, or establishing reputations as soloists on the (then) world’s most-respected concert series, Paris’s Concert Sprirituel.

The music on our program makes no apologies for its origins. Despite its genesis in an age of indulgence, it’s so much more than merely pleasing or even titillating; I hope you’ll also hear its daring, experimental side – that which locates it on the eve of an aesthetic revolution. These works from the 1740s and 1750s don’t conform to our expectations about baroque music, but they’re not quite Classical either. Rather, they mix the humor and wit of early Haydn and Gluck with some of C.P.E. Bach’s sturm und drang, adding characteristically lush French harmonies together to create a truly unique sound. The result is a fusion of baroque gestures and Classical forms that combine with harmonic and technical virtuosity to yield expressive extremes.

The music on our program makes no apologies for its origins. Despite its genesis in an age of indulgence, it’s so much more than merely pleasing or even titillating; I hope you’ll also hear its daring, experimental side – that which locates it on the eve of an aesthetic revolution. These works from the 1740s and 1750s don’t conform to our expectations about baroque music, but they’re not quite Classical either. Rather, they mix the humor and wit of early Haydn and Gluck with some of C.P.E. Bach’s sturm und drang, adding characteristically lush French harmonies together to create a truly unique sound. The result is a fusion of baroque gestures and Classical forms that combine with harmonic and technical virtuosity to yield expressive extremes.

François-André Philidor (1726–1795) was the youngest and (by some accounts) most important member of the Philidor dynasty of musicians. He composed l’Art de la Modulation (1755) before his career as a composer of Opéra Comique really got off the ground, but his fame, ultimately, rests more on his accomplishments as the first professional chess player than as a composer. His treatise on chess saw over 100 editions in at least 10 languages following its initial publication in 1749 and he could play (and win) three simultaneous games of chess blindfolded during exhibition games.

The two quartets from François-André Philidor’s l’Art de la Modulation (1755) achieve their sense of surprise and play through fast, unexpected harmonic shifts, creating a sense of fun, exploration and surprise. In Sinfonia I, the opening section (marked Con Spirito) finds the oboe and violin playing in thirds, while pungent chromatic inflections and plangent melodic intervals abound. The fugue that follows (which Philidor dubs l’Arte della Fuga) is again rife with chromatic inflections and interruptions, as well as disquieting melodic augmented 2nds. The sweet Pastorella allows for some peaceful relief : full of sonorous drones in G major, it’s part-siciliano/part-musette, But there’s trouble in paradise as wistful departures and chromatic shocks arrest the listener. The spirited Gavotta pops and crackles with excitement as it closes the work.

While Philidor moved in international chess-playing circles and spent large parts of his career in London, the other composers on tonight’s program were truly fixtures on Paris’ concert stages and in her finest salons.

François Martin’s star was extinguished before it had even reached its apex. Acclaimed as a “très excellent violoncelle,” Martin (1727–1757) was granted a privilège to publish his own compositions at the tender age of 18, acquired a coveted position as a musician at Court the following year, and, at 20, found himself performing his own cello sonatas to acclaim at the Concert Spirituel. Over the next ten years, his music (including sonatas, petits, and grands motets) were often featured at the Concert Spirituel, but it was his symphonies and overtures –complete with chromaticism, gradual dynamic shifts, rich harmonies, and written in a nascent sonata form – that were particularly fashion-forward. The sonata in b minor from his 1746 Op. 3 Conversations à 3 is playful, exploratory, and very much in keeping with the conversational style of Paris’ cultivated salons.

Michel Blavet (1700–1768) moved to Paris from Besançon at the age of 23 and quickly established his reputation as the finest flutist of his generation. Following his debut at the Concert Spirituel at age 26, he appeared more regularly than any other soloist. By 1736, he entered the service of the King but continued to perform both publicly and in Paris’ elite salons, premiering important works (such as Telemann’s famed Paris quartets – along with violinist Guignon and viola da gamba player Forqueray). He was renowned for marrying incredible refinement and expression with a virtuoso technique that was inspired by the Italian violin school. His famous Op. 2 no. 2 sonata “La Vibray” reflects Italian extroversion in the lively Allemanda and final Allegro, while the opening Andante (prelude) and the Gavotta “les Caquets” require incredible sensitivity and a particularly French sensibility.

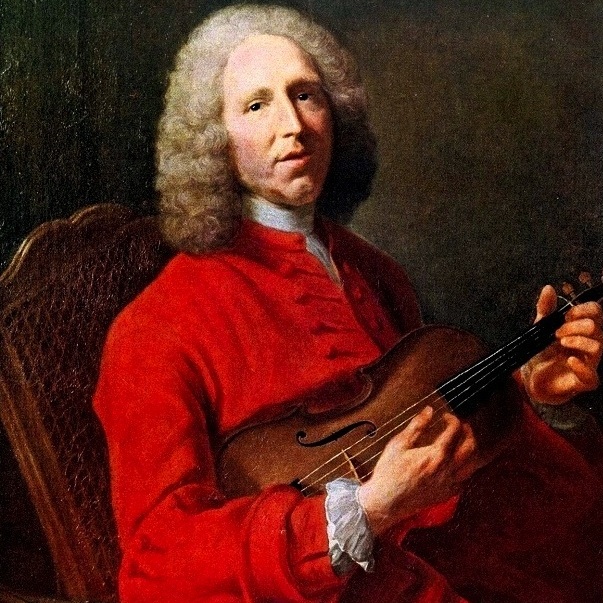

Like Blavet, Jean-Philippe Rameau (1683–1764) moved on from provincial posts as an organist and church musician to make a name for himself in Paris. Once there, he received a huge professional leg-up from the patronage of tax-farmer Alexandre La Riche de la Pouplinière.

Rameau’s Pièces de Clavecin en concert (1741) respond to contemporary Parisian trends in clearly taking a 1734 set of harpsichord sonatas with violin accompaniment by Joseph-Cassanea de Mondonville as their inspiration. Set for obbligato harpsichord with violin and viola da gamba (or optional 2nd violin or flute), Rameau’s harpsichord part demands a unique virtuosity and flair that’s supported and enriched by the bowed strings. Rameau’s 3eme Concert betrays a particular debt not only to his personal patron but also to Rameau’s own operatic output. The opening movement, La Lapoplinière is either a direct tribute to La Pouplinière or a dedication to his wife, who was an accomplished keyboardist and student of Rameau’s. The wonderful rondeau theme of La Timide is borrowed from a charming air gracieux that had recently been heard in Rameau’s opera Dardanus (1739), while the visceral, fun Tambourins were heard first in Rameau’s Castor et Pollux (1737).

It was in preview performances featuring La Pouplinière’s house chamber-orchestra that Rameau’s operas were first heard by cognoscenti and taste-makers. Echoing the spirit of chamber arrangements of excerpts from Rameau’s operas (such as his own collection of Grand Concerts from Les Indes galantes) as well as contemporary arrangements by others (such as those by the Prussian viol virtuoso Christian Ludwig Hesse), we have adapted selections from Rameau’s operatic oeuvre to our ensemble.

Rameau’s final opera, Les Boréades (1763), was never produced in the 18th century. The autograph score that survives, however, contains remarkable music. The frequent hestitations of the Air gracieux make us imagine a fanciful staging, while the Entrée de Polymnie – replete with cascades of flowing scales and beautiful, layered suspensions – approaches the sublime. The perfumed Sarabande that follows in our suite is taken from Rameau’s little-known ballet-héroique, Les Fêtes de l’Hymen (1747).

The famous tune Les Sauvages was penned by Rameau around 1725 or 1727 upon witnessing the ceremonial dancing of two Native Americans who were visiting France. Originally composed as a keyboard solo, the tune became wildly popular. Rameau reused it in his own opera-ballet Les Indes galantes (1735) and it was adapted by many other composers. Jean-Pierre Guignon (1702–1774) published two books of violin duos that present variations on famous tunes, the first of which concludes with this wonderful setting of Les Sauvages. His preface informs us that he performed them with his colleague Mondonville at the Concert des Tuilleries. The product of formative training in Italy with the Turin-based violinist Giuseppe Somis, Guignon rose to fame as a featured artist at Paris’ Concert Spirituel. He was well known not only for performing his own works but also as frequent soloist for Vivaldi’s Four Seasons. Like Blavet, Guignon also worked in the most elite musical circles (his patron was the Prince de Carignan) and he premiered works by Rameau and even Telemann’s Paris Quartets.

We close our program with Philidor’s Symphonie V from his l’Art de la Modulation. Like the first piece on our program, this quartet achieves a sense of play through fast, unexpected harmonic shifts. The warmth and ease of the opening C-major Adagio quickly gives way to diminished harmonies and chromaticism while the jaunty Fuga modulates (briefly) as far as Db major(!). Peace is restored in the minuet-like Andante and the quartet ends with a playful yet virtuosic theme and variations.

* * *

SFEMS presents Agave Baroque with Reginald Mobley at 8:00 p.m., Friday, March 2, at First Presbyterian Church,1140 Cowper Street (at Lincoln) in Palo Alto; 7:30 p.m., Saturday, March 3, at St. Mary Magdalen Parish, 2005 Berryman Street in Berkeley; and 4:00 p.m., Sunday, March 4, at Church of the Advent, 251 Fell Street in San Francisco. Note the non-standard venues for our Berkeley and San Francisco concerts. Tickets are available online or through the SFEMS Box Office at 510-528-1725.