by Karen R. Clark

The SFEMS concert series resumes the weekend of January 5–7 with a warm welcome to the New Year. The “elegant, full-blooded” singing of Vajra Voices and zesty, vibrant harp and vielle playing of Shira Kammen join together with the recorder, psaltery, and magic of Kit Higginson to illuminate the mystery and wonder of the new year. Vajra Voices’ program boasts florid medieval chant, luscious French motets, chansons of Machaut; and beautiful Middle English poems told in enchanting settings and enhanced by a bit of mystery.

SFEMS Affiliate Vajra Voices was founded and is directed by contralto Karen R. Clark. Also featuring singers Allison Zelles Lloyd, Amy Stuart Hunn, Cheryl Moore, Lindsey McLennan Burdick, Phoebe Jevtovic Rosquist, and Celeste Winant, the group sings medieval to modern music in a style inspired by Hildegard von Bingen, one that is “clear, sweet, and strong.” Vajra Voices debut recording, O Eterne Deus: Music of Hildegard von Bingen with instrumentalist, Shira Kammen, was called “the most convincing Hildegard disc yet from the USA” by Choir & Organ Magazine. This season Vajra Voices singing of rhapsodic chants in praise of the Divine Feminine provided inspiration for the sumptuous choreography of Garrett & Moulton’s, Divining, which premiered in Oakland Ballet’s production, A Capella: Our Bodies Sing. Vajra Voices also presented “A Medieval Veneration of Mary” on the full concert series, in the new Berkeley Art Museum Pacific Film Archive.

Join our celebration of new beginnings that hearkens back to the magic of Winter’s light. Festive attire is suggested! Director Karen Clark introduces the works to be performed in the context of the program’s design.

Welcome! Annus Novus in Gaudio! The new year celebrates new beginnings and is reflected in the medieval texts as restoration after destruction, redemption after the fall, and radiant light springing forth out of darkness. Similar to the ancient Chinese principle of yin-yang that posits the dynamic balance and overarching wholeness of all things, our program, Annus Novus: One Yeare Begins, centers around the restorative power of time’s inevitable orbit.

In the florid organum Gaudia debita temporis orbi, time’s orbit restores joy to the world. It is the “new” Adam (Christ) who repairs what had been damaged by the old “alter” Adam. In Hildegard von Bingen’s O quam mirabilis est, all creation is in God’s prescience (mirabilus est prescientia divini). “When God looked on the face of the human He had formed, He saw all his works whole.”

Wholeness finds expression in devout medieval texts wherein the spiritual and sensual commingle freely. “The King enters the docile female form” in Hildegard’s antiphon for the Virgin, O quam magnum miraculum est. And in O splendidissima gemma, “the sun pours into you, a fountain springing from the Father’s heart; and the Word (Christ) breathes forth the primal matter of all creation, and all virtues.” In the celestial hierarchy of divine virtues, Sapientiae (Wisdom) and her closest sister, Karitas (Divine Love) have existed since the dawn of all time, independently of the accidental structure of the world. In Hildegard’s first book, Scivias (Know the Ways of God), she writes that Sapientiae “was in the most high Father giving counsel in the formation of all creatures made in heaven and earth…joined to him in a sweet embrace of ardent love.” Furthermore, it is Karitas who “gives the high King the kiss of peace.”

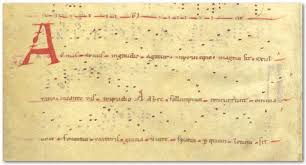

Hildegard’s evocative and highly melismatic free verse settings are contrasted with the rhymed, more concise verse found in the roughly contemporary St. Martial style. Gregorian chant forms the basis for the earliest polyphonic music found in the St. Martial de Limoges manuscripts. This collection contains two distinct styles: 1) florid organum (Gaudia debita temporis, Mundo salus) wherein the upper melismatic voice is guided by the more stable lower line; and 2) discant style, wherein two or three (equal) voices move together (Annus novus in gaudio and Verbum patris humanatur). This conductus Verbum patris happens to be one of the earliest surviving three-part pieces of music.

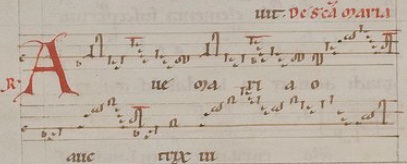

Interestingly, since rhythm (as we think of it) is not indicated in either St. Martial or Hildegard von Bingen’s music, or indeed in any written music before about 1200, we have taken the inflection of the text to be the rhythmic determinant. That, and knowing the intervals that were considered to be consonant — the unison, the octave, the pure fifth and fourth, and to a much less extent, the thirds — helps guide us in determining rhythm. In Aquitanian notation, pitch relationships were indicated by dots and occasionally pitch names carefully arranged around one line. Hildegard von Bingen’s 12th Century notation uses a 4-line staff with clef indications (c and f) and neumes indicating the number of tones per syllable.

Two centuries later, composers were creating complex, polyphonic musical structures by building upon these pre-existing chant lines. The chant melody, the tenor, becomes the sustaining (organizing) element in polyphonic music. By 1200, a system of rhythmic modes had been developed which provided a way to notate rhythm.

We open our second half with a wonderful piece by Perotin, who was the first indisputably great composer to benefit from the invention of a more determinative notation for rhythm. Perotin’s discant clausulae characteristically contain highly metric upper voices over extremely long notes, derived from Gregorian chant, in the tenor (literally, held part). A perfect example of Perotin’s art is the Alleluia: Nativitatis, celebrating the birth of the Virgin Mary.

Gregorian chant extends its influence into a highly significant musical form of the thirteenth and fourteenth century known as the motet. The musical texture of the medieval motet is obviously descended from Perotin’s groundbreaking structures, but the upper parts (triplum and motetus) show decidedly greater independence from one another, having not only contrasting rhythms but even different texts. Most often, the texts of these upper lines are secular.

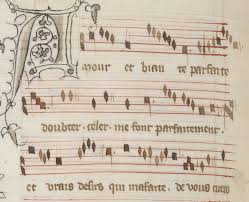

In Machaut’s Quant en moy/Amour et biauté/Amara valde, the poems in the upper parts express the bittersweet pain of longing in unrequited love, a common chivalric theme. Blending the spiritual and the sensual (with a dose of humor), these voices move above the Gregorian tenor Amara valde (“very bitter”) extolling the honor of noble unfulfilled desire. Similar to earlier medieval texts, the line between chivalric devotion and praise of the Virgin Mary has blurred.

Our program offers one example of the formes fixes — poetic forms (rondeau, virelai and ballade) frequently used in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries primarily by French composers. In the rondeau Ma fin est mon commencement, Machaut exhibits his skill and wit by creating a text that literally describes this cyclical musical structure. In this three-voice piece, the upper two voices — the triplum and cantus — are identical yet sung in exact retrograde of one another. The third voice, the tenor, exactly reverses itself at the mid-point of the piece. Significantly, Machaut’s tenor is now freely composed; it shows not a trace of chant DNA.

The three pieces we’ve selected from England (Ther is no rose of swych vertu, and Hayl, Mary, full of grace and Alleluia, a nywe werk) are each inspired by thoughts of renewal. The first two are from the Trinity Carol Roll, a parchment compiled in the early fifteenth century. (The Carol Roll references the Battle of Agincourt of 1415.) The third piece is a carol from the Selden Choral Book. With the carol Ther is no rose of swyth vertu, we return to a contemplation of the joy and mystery of life: “For, within the small space of a rose, exists all of Heaven and Earth.”

It happens that much of the music on today’s program spans the construction of the Cathedral of Notre Dame de Paris, and more somberly, the era of the Holy Wars. It is also the time when the cities of Bologna, Paris, and Oxford established the first universities. Our modern minds marvel at the complexities and contradictions of this period of time. Our awe, perhaps, stems from what we perceive of the medieval mind — the hallowed grandeur of the cathedrals, the sonorous musical intricacies first formed in the imagination, then, rendered pen to parchment — minds that reflect the infinite possibilities within the human soul. For, within time’s orbit, it does seem we get to begin anew.

In Gaudio Novus Annus!

* * *

FRIDAY, JAN 5, 8:00PM

First Presbyterian Church

1140 Cowper Street, Palo Alto

SATURDAY, JAN 6, 7:30PM

St. John’s Presbyterian Church

2727 College Ave, Berkeley

SUNDAY, JAN 7, 4:00PM

St. Mark’s Lutheran Church

1111 O’Farrell, San Francisco

Tickets are available online or through the SFEMS Box Office at 510-528-1725

COME 30 MINUTES EARLY FOR A FREE PRE-CONCERT PRESENTATION

MUSIC, MAGIC & MYSTICISM: In Conversation with Karen R. Clark, Kit Higginson, and Shira Kammen