Tackling Difficulty in Renaissance Music

by Jesse Rodin

What makes a piece of music difficult? Answers can range all over—from unexpected melodic leaps to technical challenges that arise from bad composing. What’s impossible for me might be a piece of cake for you, and vice-versa. And what’s challenging today might seem straightforward after a week of practice. Difficulty is a moving target.

What makes a piece of music difficult? Answers can range all over—from unexpected melodic leaps to technical challenges that arise from bad composing. What’s impossible for me might be a piece of cake for you, and vice-versa. And what’s challenging today might seem straightforward after a week of practice. Difficulty is a moving target.

And yet surely there are some things we can all agree are just plain hard: wildly complicated rhythms, extremely wide vocal ranges, and musical notation so abstruse that it can be understood only after extended study. Even here we can run into problems putting our finger on the nature of the difficulty, particularly when we direct the conversation to music of the past. How do we know what was difficult for them—was it really the same as what’s difficult for us?

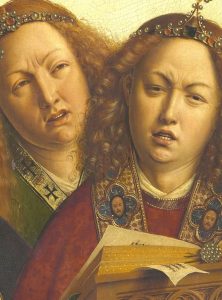

On Friday, May 31 (Hertz Concert Hall, UC Berkeley, 8:00 p.m.), the vocal ensemble Cut Circle will present “Hard Songs,” featuring music that at one time or another has given musicians a headache. Directed by Jesse Rodin (Stanford University), the concert is connected to an international conference hosted by Emily Zazulia (UC Berkeley) on the concept of difficulty in late-medieval and Renaissance music. The main questions on the table are: How should we define difficulty, then and now? How can we clear away issues like bleed-through on manuscript pages and an unfamiliarity with an old notational system in order to channel a musician for whom “complex fifteenth-century polyphony” was just “music?” How extreme did the music need to get before it was hard even for an expert singer of the period?

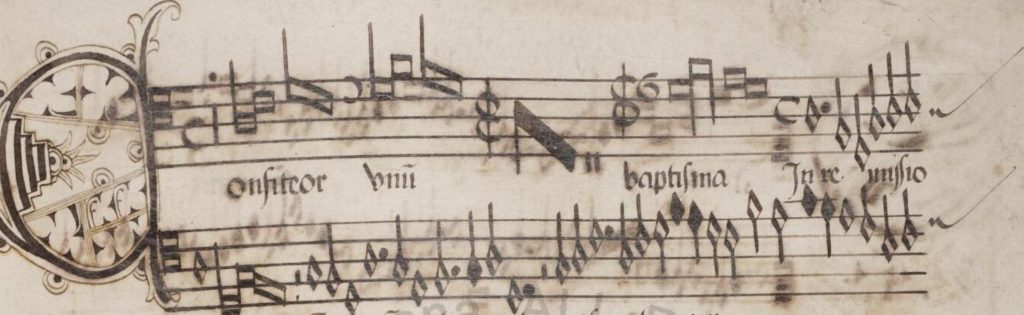

The centerpiece of the concert is the Missa L’ardant desir, an anonymous four-voice mass based on a now lost anonymous song. Part of the piece’s difficulty lies in how the composer has treated the song, which is quoted throughout by the tenor voice. Alongside not-so-very-hard moments, like when the tenor sings the tune at half the written speed, we find fairly challenging—or at least fairly weird—procedures, like an instruction to read the notation while omitting all the stems. Maybe that doesn’t seem so bad. But then how about this: in one section the tenor has to skip any note followed by a note that’s one step higher. In another, the tenor must replace each rhythmic value with its opposite (very short notes become very long, and vice versa). Through all of this the rhythms sung by the other three voices are busy bordering on bananas.

The centerpiece of the concert is the Missa L’ardant desir, an anonymous four-voice mass based on a now lost anonymous song. Part of the piece’s difficulty lies in how the composer has treated the song, which is quoted throughout by the tenor voice. Alongside not-so-very-hard moments, like when the tenor sings the tune at half the written speed, we find fairly challenging—or at least fairly weird—procedures, like an instruction to read the notation while omitting all the stems. Maybe that doesn’t seem so bad. But then how about this: in one section the tenor has to skip any note followed by a note that’s one step higher. In another, the tenor must replace each rhythmic value with its opposite (very short notes become very long, and vice versa). Through all of this the rhythms sung by the other three voices are busy bordering on bananas.

Cut Circle, which recently performed a trio of Bay Area concerts for SFEMS to critical acclaim, is accustomed to challenging music. This event will take things to a new level, as the performers, singing one-on-a-part, tackle not only the Missa L’ardant desir, but also excerpts from another hard mass (Gross senen) and songs by Johannes Ockeghem, whose music has not (so far as we know) ever been marketed to toddlers. But the main challenge the concert presents is to go beyond the difficult elements and deliver convincing, even moving performances. Most of this music hasn’t been heard since the fifteenth century. Its time has come.

Cut Circle (Sonja DuToit Tengblad, Jonas Budris, Bradford Gleim, and Paul Max Tipton; Jesse Rodin, Director) will present “Hard Songs” at 8:00 p.m., Friday, May 31, in Hertz Concert Hall, 101 Cross-Sproul Path, on the UC Berkeley campus. To purchase tickets ($10–$25), visit https://secure-tickets.berkeley.edu/14450/14451. For more information on the conference (May 31–June 1), visit http://music.berkeley.edu/hard-songs/.