San Francisco, March 28, 2015: In their now firmly established “Haydn and His Students” tradition, the New Esterházy Quartet present the alpha and omega of Haydn string quartets, opening with his “Op. 1 No. 0” and ending with Beethoven’s Op. 131, which can be considered the “farthest out” string quartet ever written by a student of Haydn.

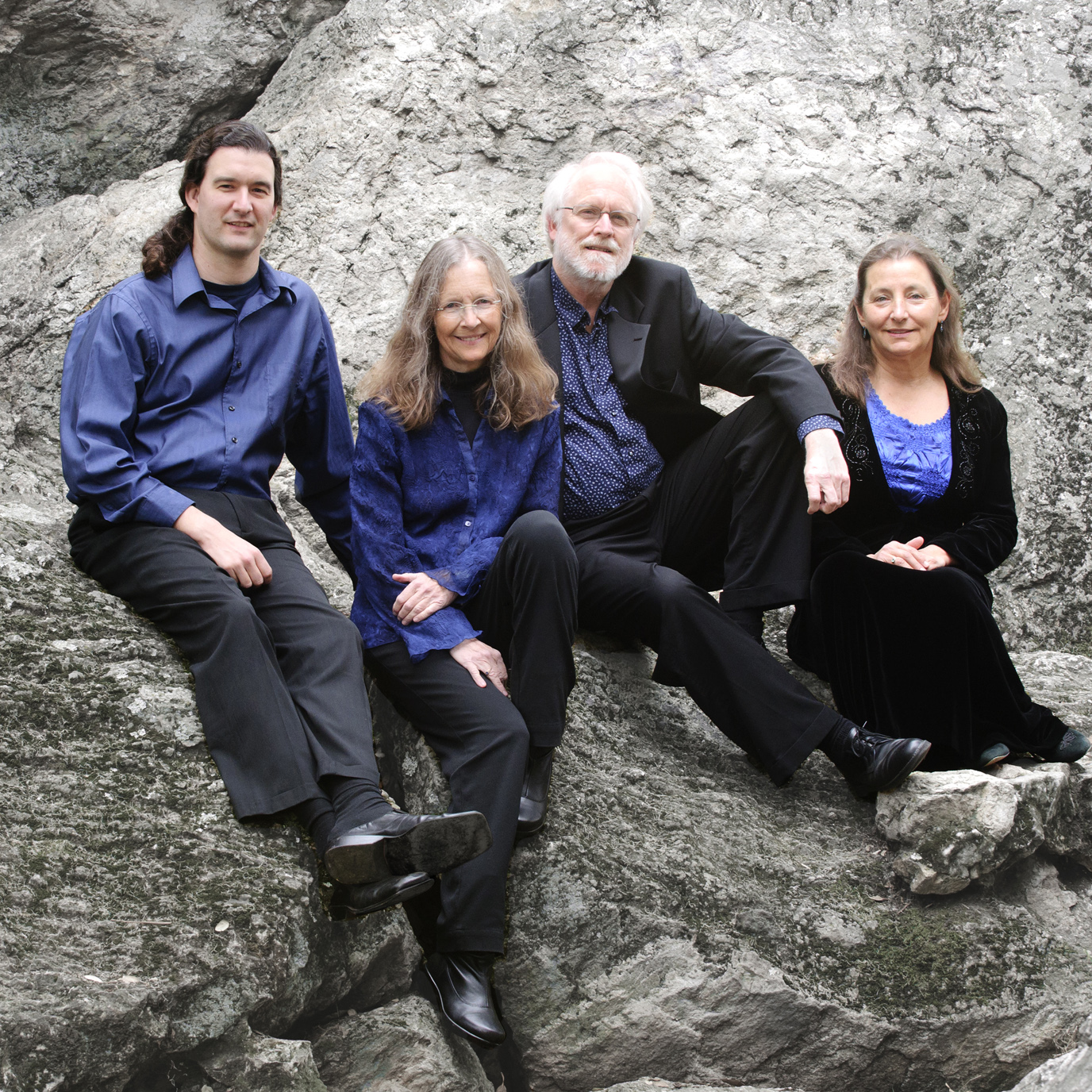

Since the fall of 2010, the New Esterházy Quartet (violinists Lisa Weiss and Kati Kyme, violist Anthony Martin, and cellist William Skeen) have performed six episodes in the “Haydn and His Students” series. Every single one of these programs featured a quartet by Haydn himself, one by Beethoven, and one by a less famous student, thus introducing Bay Area audiences to the works of Eybler, Titz, Wranitzky, Reicha, Zmeskall, Pleyel, and Lessel. This time the honor goes to Paul Struck (1776–1820), whose “Quartet in C, Op. 2” rounds out the program between Haydn’s “alpha” and Beethoven’s “omega.” Struck studied with Haydn in the late 1790s and published his Opus 1 and 2 in 1797. The first, three piano trios, was dedicated to Haydn. The second is the “String Quartet in C” on this program. Later, Struck traveled all over Europe. When in Stockholm, he helped produce the first performance of Haydn’s Creation there in 1801.

Since the fall of 2010, the New Esterházy Quartet (violinists Lisa Weiss and Kati Kyme, violist Anthony Martin, and cellist William Skeen) have performed six episodes in the “Haydn and His Students” series. Every single one of these programs featured a quartet by Haydn himself, one by Beethoven, and one by a less famous student, thus introducing Bay Area audiences to the works of Eybler, Titz, Wranitzky, Reicha, Zmeskall, Pleyel, and Lessel. This time the honor goes to Paul Struck (1776–1820), whose “Quartet in C, Op. 2” rounds out the program between Haydn’s “alpha” and Beethoven’s “omega.” Struck studied with Haydn in the late 1790s and published his Opus 1 and 2 in 1797. The first, three piano trios, was dedicated to Haydn. The second is the “String Quartet in C” on this program. Later, Struck traveled all over Europe. When in Stockholm, he helped produce the first performance of Haydn’s Creation there in 1801.

The history behind the odd opus number of Haydn’s “Op. 1, No. 0” is entertaining. When, in Haydn’s old age, his student Ignaz Pleyel (piano-maker, publisher, and sometime compositional rival) undertook to publish the collected Haydn quartets, he grouped as Opp. 1 and 2 two complements of the conventional six quartets each, which had been published as such in 1764. Unfortunately, three of these were eventually proven to have been there under false pretenses. Op. 1, No. 5 was an early symphony shorn of its oboes and horns, while Op. 2, Nos. 3 and 5, were originally sextets, with two horns. (In a couple of spots, the music had to be modified to eliminate independent horn parts, but in general they were only harmony-reinforcing.) So nine actual early Haydn quartets remained. The tenth is our Op. 1, No. 0, which remained beyond Pleyel’s ken having been published independently, also in 1764. It is alternatively called Op. 0, or Op. 1/5, repurposing the slot of the errant symphony.

To the extent to which anyone might want to think of a “first” Haydn quartet, one could hardly do better. Everything that was later to develop is, in its fashion, already there: the frolic joviality; the easy exchange of ideas among the instruments; the aria-like grace and serenity of the slow movement, with its accompaniment at once simple and intricate. All were vastly complicated and extended over the succeeding half-century, of course; but the germ of what is to come is there from the beginning.

Struck’s writing showcases clear signs of Haydnesque inventiveness. In the first movement of his quartet there’s the nagging repetition (in all parts) of two slurred notes a half-step apart, which gets launched on a major escapade in the development. Reminiscent of Haydn’s “Emperor” quartet, the slow movement is a graceful tribute to all, favors allotted in turn to the first violin, the second violin, and (in the last), cello and viola in tandem, over the course of three variations. The finale belongs, in audacity at least, in Haydn’s own rank. The first violin, as usual, carries the brunt, but there are solos for the other players, including a bristling one (heard twice) from the second violin. Even the cello gets one, in the second half.

The leap from this work to Beethoven’s Op. 131 sounds wider than its mere quarter-century of years. If Haydn’s “Op. 1, No. 0” is the beginning of a journey, Beethoven’s Op. 131 can fairly be called the end of it. Only his “Grosse Fuge” would be an equal candidate for this position. The opening fugue, solemn, cerebral and austere, dissolves with a turn of the corner into filigree, a D-major romp that evaporates into effortless hilarity. And it’s the same later on: The great central variations, after a few iterations, get so complex that they’ve essentially walled themselves in, and so Beethoven turns another corner and we’re somewhere else. And after the long end of those variations, suddenly we are in a sunlit corner of Arcadia, giddily chasing sprites in E major. In fact, the entire piece and its genesis could be heard as a paean to free will. It goes where it wants to go.

The concerts take place at 8:00 p.m., Friday, April 24, at the Hillside Club, 2286 Cedar Street (at Spruce), in Berkeley; 4:00 p.m., Saturday, April 25, at St. Mark’s Lutheran Church, 1111 O’Farrell Street (at Franklin), San Francisco; and 4:00 p.m., Sunday, April 26, at All Saints’ Episcopal Church, 555 Waverley Street (at Hamilton), in Palo Alto. Tickets for the Friday concert are $20, and sold only at the door. Tickets for Saturday and Sunday are $25 (discounts for SFEMS members, seniors and students). Call 415-520-0611 or visit www.newesterhazy.org.