A Gift from Frans Brüggen and Lee McRae

by Peter Fisher

On Saturday, September 23, 2017, Eva Legêne produced a memorial celebration at St. John’s Church in Berkeley for Lee McRae, a remarkably accomplished musician, teacher, worker for peace and justice, and a dear friend to many Bay Area musicians. The following are remarks I prepared for that lovely occasion:

In 1973, I was a grad student supporting myself as a flutist playing street music in San Francisco’s Union Square with a harpsichordist and cellist, calling ourselves the Berkeley Street Ensemble. We saw a flyer for an eight-day seminar and masterclass at UC Berkeley led by Frans Brüggen and Alan Curtis focused on J.S. Bach’s Sonata for Flute and Harpsichord in B Minor, and since Bach’s sonatas were the core of our repertoire, we dipped into our bag of quarters and signed up. It was my first contact with Lee McRae who, as Brüggen’s American agent, produced the event. Brüggen’s lecture titled “How to Play Expressively on the Recorder” has shaped my musical life, and I’ve often returned to my notes.

In 1973, I was a grad student supporting myself as a flutist playing street music in San Francisco’s Union Square with a harpsichordist and cellist, calling ourselves the Berkeley Street Ensemble. We saw a flyer for an eight-day seminar and masterclass at UC Berkeley led by Frans Brüggen and Alan Curtis focused on J.S. Bach’s Sonata for Flute and Harpsichord in B Minor, and since Bach’s sonatas were the core of our repertoire, we dipped into our bag of quarters and signed up. It was my first contact with Lee McRae who, as Brüggen’s American agent, produced the event. Brüggen’s lecture titled “How to Play Expressively on the Recorder” has shaped my musical life, and I’ve often returned to my notes.

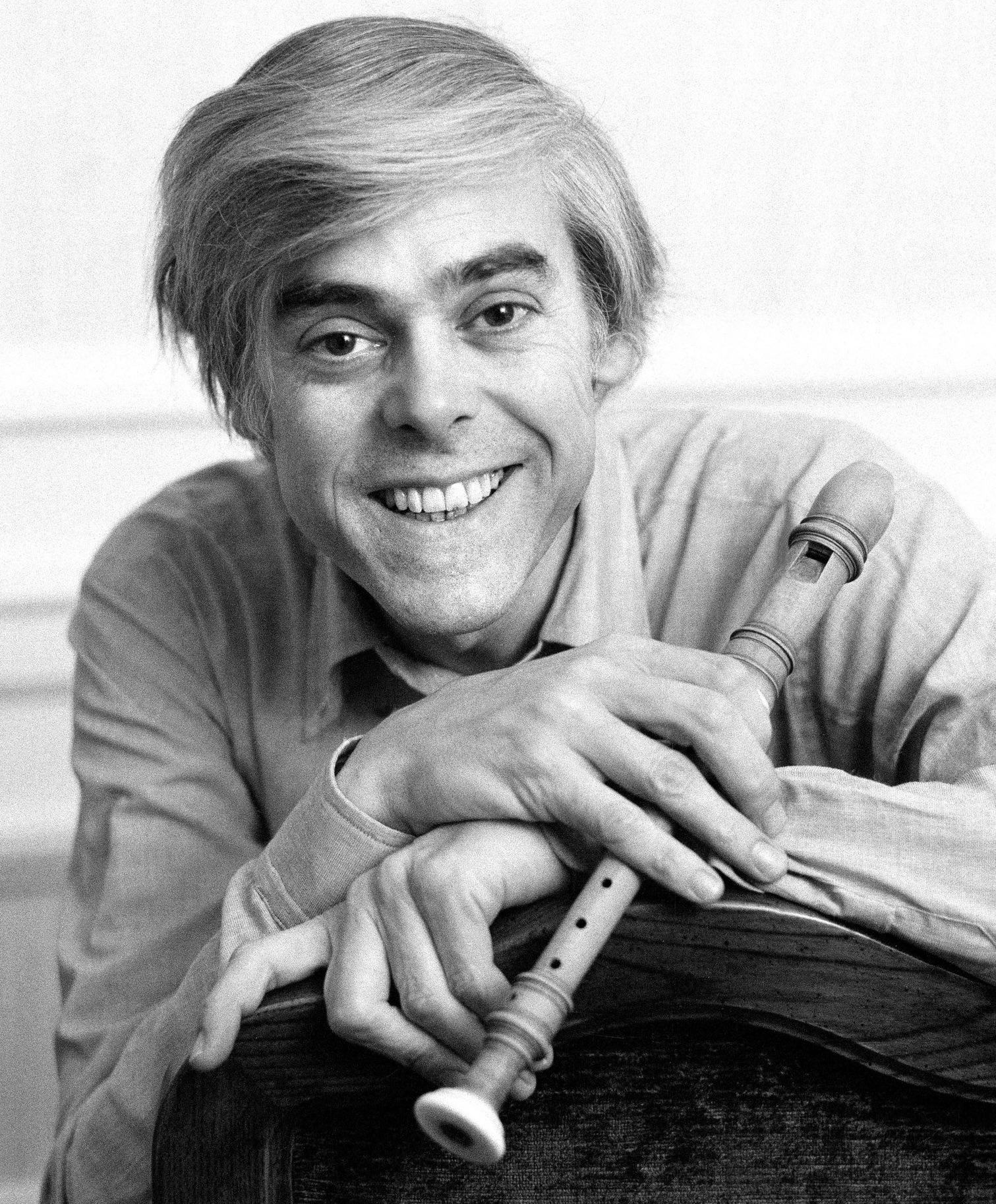

Lee’s life encompassed almost all the early music revival in America. She worked with LaNoue Davenport, who led the pioneering professional ensemble New York Pro Musica Antiqua after Noah Greenberg passed away, and represented Davenport’s group Music for A While. She promoted many early music artists, but her relationship with Frans Brüggen was special. Those of you younger than 50 may only know Brüggen as conductor of the Orchestra of the 18th Century, but in 1973 he was at the height of his career as a recorder and flute virtuoso. Lee and Frans were not only business partners, but real friends, sharing a life-long commitment to bringing the music of the past to life.

At this point Lee would probably say, “Peter, that’s enough about me. Share your lecture notes, and get off the stage.” O.K., Lee.

* * * * *

How to Play Expressively on the Recorder

(according to Frans Brüggen in 1973)

“It’s impossible to describe in words, but it’s a subject that should be attempted occasionally.

“One needs a clean clear knowledge of what is not expressive. Playing old music is on the edge of perversity. The Romantics developed the notion of playing old music, as in Mendelssohn’s St. Matthew Passion revival in 1829. Before then musicians played at most music one generation old–‘father’s music.’ Earlier musicians weren’t artists, but craftsmen, officers of court, churchmen, street entertainers. They had no vanity, no sense of art. Looking into the past (or the future) is the sign of a weak culture, slightly perverse.

“What makes music expressive in performance? What makes things expressive in any aspect of life? These are the common factors:

Sheer mechanical perfection. The perfect use of utensils is always astonishing, and very expressive, whether by musicians, mechanics, cooks, etc. The shock of perfect craftsmanship is always expressive and seems to be a personal message.

Innocence. Pleasance is not enough. Someone who wants to be pleasant is always a fake, and generally wants to please only himself. A child, up to about age 3, is automatically expressive, because he lacks vanity. Everything an animal does is expressive.

Realization of full potential. It’s described by a Dutch word that transliterates as “richdom.”

Danger. In this bourgeois society a living room with a brightly burning fireplace is considered expressive. What would be really expressive is a brightly burning living room.

“A word about style: Stylistic features in music are not expressive, and have nothing to do with expression. It is desirable to play stylistically only when it is not frustrating to more important things.

“Zo: Perfection + Innocence + Full Potential + Danger = Nature.

“Nature is by nature expressive. Therefore, whatever is natural is expressive.

“It is always our vanity, lack of skill, bourgoisedom, and the literature which keeps us from playing expressively. It is very unnatural to play someone else’s music. It’s the literature that keeps us away from our own talent, our natural ability to play, that everyone possesses.

“A lot of adults seem to have lost contact with what they’re doing. The only true reason to play is not that you want to play Bach sonatas, but that you love the instrument and need to be in constant contact with it. The literature is distracting from the talent. Pianists want to hammer. String players who are only interested in the left hand are on the wrong track–the right hand, the bowing, tone-producing hand, is where the soul is. An oboe player needs a trembling reed between his lips, a flute player the special configuration of the embouchure and the tone hole, a harpsichordist the plucked string. One should ask every day why he plays.

“The need for 18th-century music, the need for style, the need for correctness, are all wrong reasons to play. Once you reach IT, everything becomes easy, the technical problems, the need for labor goes away, everything is pleasant. Things become their essence. Things in themselves are always simple. To regard things as difficult is the sign of a bad conscience.

“The tricks are to be learned only after one has perceived the essentials. To start with style is 100% wrong, because it is 100% vain. What to do is give it time–not two or three years, but 15, or a lifetime.”

Thank you, Lee and Frans.

* * * * *

Peter Fisher has given it 60+ years, and will present progress in a Berkeley Festival Fringe recital of Bach’s and Telemann’s flute and continuo pieces and cantata arias with obbligato, with harpsichordist Nina Bailey, cellist Paul Hale, and soprano Kaneez Munjee on June 6 at 4:00 p.m. in the Drawing Room of the Berkeley Women’s City Club on Durant St.