Instrumental music by Handel, Rameau, and Bach

For our January concerts, SFEMS welcomes back one of the newer American early music ensembles, one that deservedly has earned praise both here in its home town (New York City), and which we expect will soon will have a much wider audience. House of Time (Gonzalo X. Ruiz, oboe and recorders; Tatiana Daubek, violin; Beiliang Zhu, cello; Avi Stein, harpsichord) is comprised of some of the leading period instrument musicians in the US. Members include Juilliard faculty and graduates as well as prize-winners of major international competitions. Tatiana Daubek, violinist, is known for her expressive and personable performances. Critics have called oboist Gonzalo Ruiz “one of only a handful of truly superb baroque oboists in the world” (Alte Musik Aktuell). Harpsichordist, Avi Stein, one of NYC’s finest, is described by The New York Times as “a brilliant organ soloist” and Beiliang Zhu, is described by The New Yorker as “elegant, sensual and stylishly wild.” We are proud to say that both Gonzalo and Avi have strong Bay Area connections—in fact both attended our SFEMS summer workshops.

The group is currently in their fourth season as ensemble in residence at Holy Trinity Lutheran Church on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. The ensemble has been presented by our own Berkeley Early Music Festival, by the Czech Center New York, and by the Early Music Festival: NYC. They regularly give free outreach concerts at Mount Sinai Concerts for Patients in New York City.

Those privileged to have heard House of Time at the 2014 Berkeley Festival were unequivocal in their enthusiasm, and we hope many more in our community will discover what powerful and imaginative interpreters of baroque music they are. Their SFEMS concerts will feature theatrical music or music inspired by theater from three of the baroque era’s greatest composers. The following notes discuss these works, their theatricality, and their meaning to baroque audiences and to us today.

* * *

We may never be able to experience the theater as did audiences in the eighteenth century. In spite of titanic efforts by various organizations in presenting historically accurate opera productions, to viewers raised on Hollywood, stage machinery can never be more than quaint. For listeners used to being able to play a Mahler symphony (or anything else) in one’s own car, the simple fact of dozens of top performers assembled for a common purpose can never have the same impact as it once did. We may greatly enjoy the professional baroque dancing that is nowadays rightly included in many productions, but because it is not a better, more elaborate version of the same type of dancing we do in our own social circles, our experience of it is more distant. The only aspect of the baroque stage that comes to us with undiminished power and eloquence is the music itself, something that may once have been conceived as part (albeit central) of a multidimensional experience, but which now can stand alone as a cherished part of our own culture.

Handel composed Il Pastor Fido in 1712 in London following the great success of Rinaldo. Like its predecessor, it is an opera seria, but a relatively short one, and concerned not with gods or heroes, but with pastoral, Arcadian themes. Perhaps this is why it did not meet with the success Handel hoped for. It 1734, however, he restaged it, this time adding an entire large scale prologue dedicated to the muse of dance: Terpsichore. In this version it proved a hit and enjoyed a run of thirteen performances. Many of the newly composed dances found their way into other Handel works over the years. It is from this final version that we have selected the movements that make up the three suites included in this program.

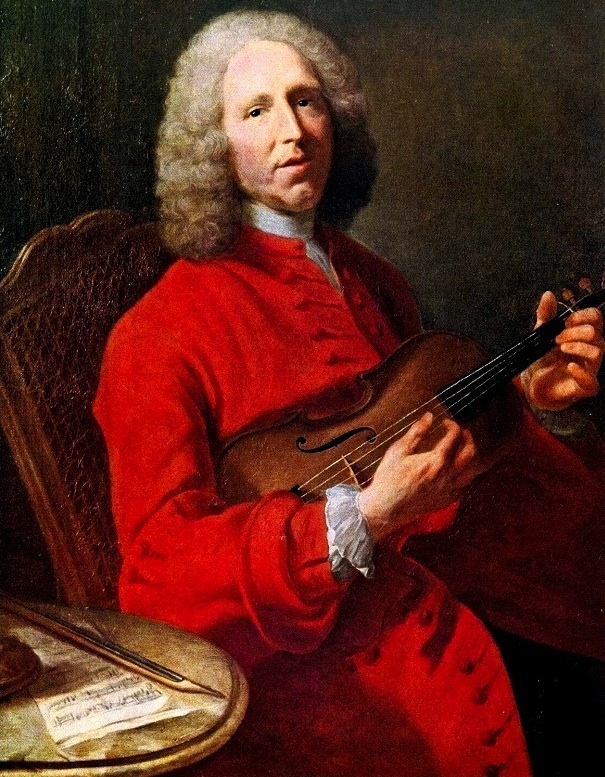

In 1738, Jean Féry Rebel composed one of the truly visionary works of the eighteenth century, Le Chaos. In this piece the creation of the world is depicted in music, proceeding from chaos to the formation and interaction of the four elements. The incomparable Jean-Philippe Rameau, not to be outdone, produced his own musical version of the creation ten years later in the overture to Zaïs. Anticipating modern scientific thought, his universe begins with a big bang, literally. The stark, brutal part played by the side drum is like the primeval sludge from which harmony, as symbol of order, attempts repeatedly to organize itself. When the long delayed, highly anticipated first real cadence finally arrives, the allegro is launched with the rhythmic propulsion and harmonic richness that are the hallmarks of Rameau’s best work. Like all of his stage works, Zaïs includes dozens of instrumental bits from which we were hard pressed to pick our favorites to make up this suite.

The organ has been called “the universal instrument” for the completeness of what a performer can achieve using both hands and feet, for the sheer variety of sounds it can achieve, so many of which imitate other instruments, and for the richness of its repertoire, at the apex of which stands the music of Johann Sebastian Bach. Bach never wrote for the stage, although he wrote fondly of the opportunities he had to experience opera in Dresden. Nevertheless, his music is often imbued with real theatricality and drama, and perhaps more than any of his contemporaries, he relied on, and appealed to, the listener’s imagination to complete some of his works. The cello suites consist of a prelude and a sequence of French courtly dances, but scored as they are for a single instrument, the elements of harmony, counterpoint, and public social dancing, cannot be fully spelled out. Instead, Bach’s writing is so richly suggestive that in a good performance one need only add a little imagination to conjure up a whole orchestra, and single instrument can make a listener want to dance.

SFEMS presents House of Time at 8:00 p.m. Friday, January 20 at St. Mark’s Episcopal Church in Palo Alto; at 7:30 p.m. Saturday, January 21 at St. John’s Presbyterian Church in Berkeley; and at 4:00 p.m. Sunday, January 22 at St. Mark’s Lutheran Church in San Francisco. Order tickets online, or phone the SFEMS Box Office at 510-528-1725.