Helping Others Discover Early Music

The death of Lee McRae on June 1, a few weeks before her 93rd birthday, adds a bittersweet touch to the San Francisco Early Music Society’s 40th anniversary and to this year’s Berkeley Festival, just two of the many institutions to which she contributed, but it also gives us a chance to review and reflect upon the career of a remarkable woman whose work and advocacy for early music had a profound effect in ways probably few readers may appreciate.

The death of Lee McRae on June 1, a few weeks before her 93rd birthday, adds a bittersweet touch to the San Francisco Early Music Society’s 40th anniversary and to this year’s Berkeley Festival, just two of the many institutions to which she contributed, but it also gives us a chance to review and reflect upon the career of a remarkable woman whose work and advocacy for early music had a profound effect in ways probably few readers may appreciate.

A founding member of our Society, Lee also founded or co-founded the SFEMS Music Discovery Workshop and the Singers’ Retreat, and she was a driving force in bringing early music not only to the Bay Area but to the whole of America. Her work, which spanned more than 5 decades, was instrumental in bringing music to thousands of children in California, Nevada, and Arizona, through her own teaching, lecture-demonstrations, publications, and the education committees she helped set up through Early Music America, the Viola da Gamba Society of America, Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra, and the Berkeley Festival. She was almost as influential behind the scenes as an artist’s representative for many of the pioneering European figures in early music, giving audiences across America the chance to hear these great artists in live performance.

Lee traced her own interest in early music to a music teacher in a Nebraska high school, who introduced her to madrigal singing and Elizabethan music. When she moved to the Bay Area with her husband and four children in the mid-1950s, they were dismayed to find the public schools here had no art, dance, or music programs, which they thought were crucial to children’s education. So, with a number of interested families they founded the Walden School, a private, alternative elementary school in Berkeley, which continues to this day as the Walden Center and School.

Lee taught at Walden for 15 years, and it was that experience which helped shape her ideas about early music education. In order for children to learn music, or about music, she decided, they need not only to hear it; they need to sing it, to see it, and even to dance to it. Getting the whole person, the whole body involved was crucial. Beyond that, she explained in a May, 2000 interview with the SFEMS Early Music News, “It’s the context, the history of it, that makes music meaningful to children. If you just hear a song or a piece of music being played, you don’t get connected to it, unless the story grabs your attention in some way.”

It was also during those early years that she became involved with the beginnings of the Bay Area’s early music community, continuing to sing madrigals and playing in a broken consort with friends. She also was a founding member of the San Francisco Early Music Society and wrote our first successful grant proposal.

Around 1975, she organized a week-long seminar at UC Berkeley, in which Alan Curtis and Frans Brüggen did a series of lectures and masterclasses, ending with a concert in Oakland. I believe this was the same masterclass at which then recorder student Bruce Dickey played a Frescobaldi canzona and was admonished by Brüggen to imagine what the work might have sounded like on the cornetto, the instrument for which it had been written, adding offhandedly, “Of course, no one can play it on cornetto today.” Thus, in a completely unintended way, Lee helped plant a seed whose germination fundamentally transformed early music’s instrumentarium and our understanding of Renaissance and early baroque music, and whose fruit we will enjoy in abundance at the Berkeley Festival.

Obviously pleased with how the event had gone, Alan Curtis asked her to be their agent. At first the prospect appalled her. “I knew nothing about being an agent,” she said, laughing. “And everyone I talked to said, ‘Don’t do it! You’re not appreciated enough for your work, and you’re not paid enough for your time.’ But after awhile, I decided that if I didn’t do it, I wouldn’t be able to hear their concerts.” So she relented and soon found herself representing the biggest names in European early music, including Brüggen, Anner Bylsma, Gustav Leonhardt, the Kuijken brothers, and more. “I booked them all over the country,” she recalled. “And I’m sure it was the first time audiences in any of those venues had heard live performances of that caliber—which no doubt made quite an impact on their perceptions of early music.”

In 1978, Lee attended the first Cazadero workshop, organized by Laurette Goldberg (Cazadero was the forerunner of the SFEMS Summer Baroque Workshop). “It was such a wonderful week, with people like Philip Brett, Bruce Haynes, and Eva Le Gêne,” she recalled. “And the levels of energy and enthusiasm were so high, that afterwards, Laurette went around and asked a few of us what we thought about starting a baroque orchestra in the area. And so we became the founding Board of Philharmonia, with Laurette as Artistic Director. And for years, while I was on the board, I kept saying, we need an education committee and outreach programs for this orchestra. But even before we had such a committee, we were able to do a couple of outreaches on tour. And we had at least one very happy result in Bakersfield, where Laurette had agreed to do a concert for students, and one young person in the audience decided then and there that the harpsichord was going to be his instrument.” That’s just one small story of how young people can be influenced by this kind of introduction to early music.”

In 1978, Lee attended the first Cazadero workshop, organized by Laurette Goldberg (Cazadero was the forerunner of the SFEMS Summer Baroque Workshop). “It was such a wonderful week, with people like Philip Brett, Bruce Haynes, and Eva Le Gêne,” she recalled. “And the levels of energy and enthusiasm were so high, that afterwards, Laurette went around and asked a few of us what we thought about starting a baroque orchestra in the area. And so we became the founding Board of Philharmonia, with Laurette as Artistic Director. And for years, while I was on the board, I kept saying, we need an education committee and outreach programs for this orchestra. But even before we had such a committee, we were able to do a couple of outreaches on tour. And we had at least one very happy result in Bakersfield, where Laurette had agreed to do a concert for students, and one young person in the audience decided then and there that the harpsichord was going to be his instrument.” That’s just one small story of how young people can be influenced by this kind of introduction to early music.”

Lee had decided by this time that early music education issues were of interest to adults as well as children, so she wrote and was awarded several National Endowment for the Humanities grants, as well as California Council for the Humanities, Nevada Humanities Committee, and Arizona Humanities Committee grants, for adult education outreach featuring early music. One was called “Quest for the Middle Ages,” a series of three lectures by university professors as well as a demonstration concert by her group, The San Francisco Consort. Other programs were “Quest for the Renaissance” and “The Reign in Spain,” the latter chronicling the hundred years from Ferdinand and Isabella through the expulsion of the Jews to the bankruptcy of Spain under Philip II.

These programs also led Lee to write a Handbook of the Renaissance, which has gone through at least 4 editions. “When I wrote the NEH Renaissance grant,” she said, “I emphasized how important it is to get all of the humanities—the whole context, not only of history, but of literature and art and music, which are all disciplines of the humanities—into the ears and bodies of children; and I said, I’ll write a handbook of the Renaissance, and they funded us; they funded 300 copies to go to the Claremont Middle School in Oakland. My idea was that each student should get a copy to keep. But when the unit was over, the teachers wanted to keep them. I got one of the nicest compliments from one of the teachers, who said the students didn’t deface this book—which is pretty rare.”

Lee continued to write resource guides and classroom units for elementary and middle school teachers, some on her own, others under the auspices of the Early Music America Education Committee: “What I kept stressing [to the EMA board] was that we needed curriculum units for teachers, so that they wouldn’t have to research everything on their own but could take what they wanted from such an outline and use it in the classroom. I’d already written a unit on the Cantigas de Santa María for 7th grade, which is when the schools in California teach medieval and Renaissance history. This was presented by the Clio Project (one-day seminars in history curriculum for teachers) sponsored by the UCB Graduate School of Education. I wrote the unit and Bob Dawson helped me teach the teachers two cantigas that day. The unit on Alfonso had background reading for the teachers, extension activities, illustrations, a couple of the cantigas themselves, and an introduction to medieval music for the students. I donated this to two important educational institutions: Arts Edge at the Kennedy Center in Washington DC, and ERIC (Educational Resources Information Center), which is the largest educational resource in the world, both of which put it out for teachers. And I also donated it to EMA, which made it available.”

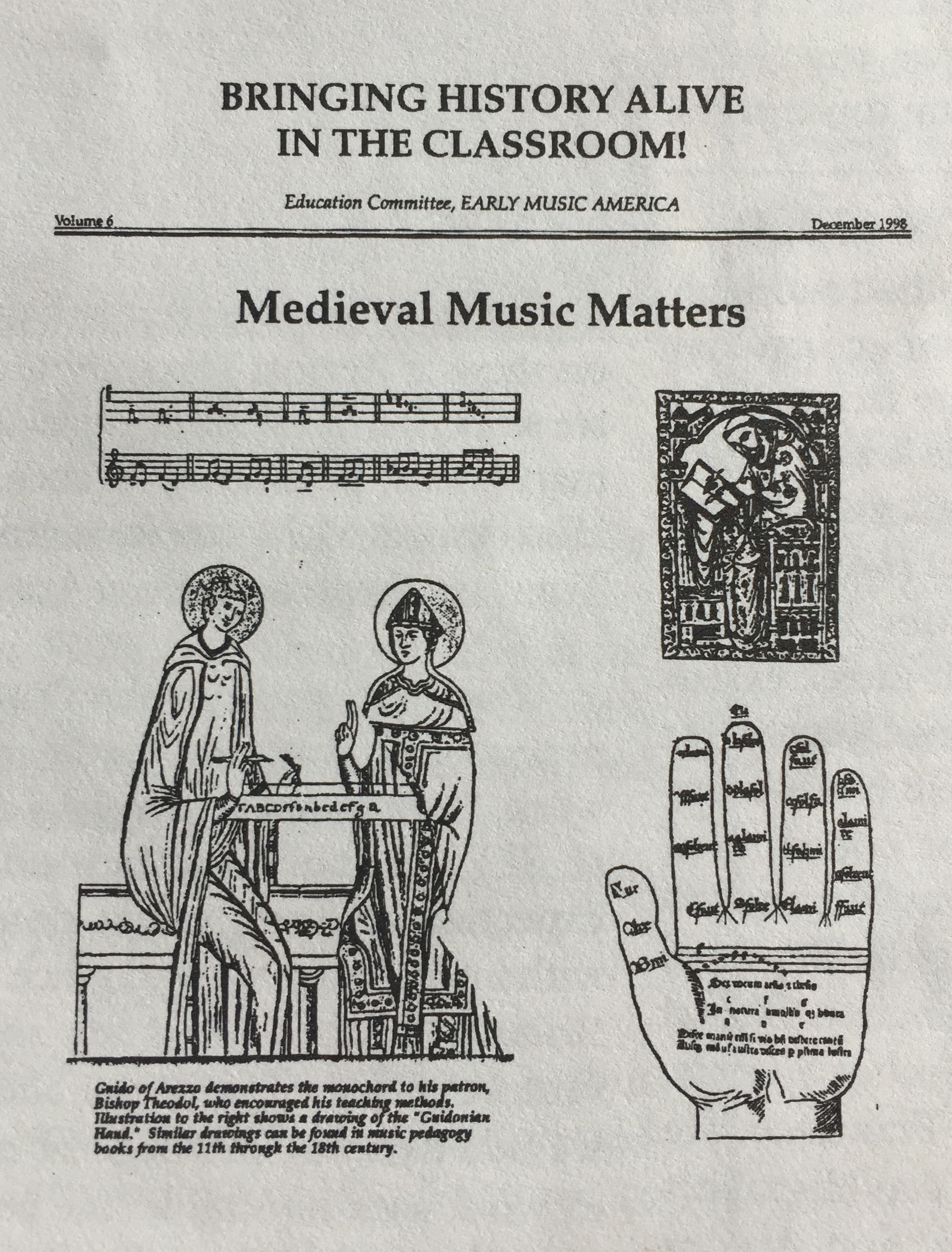

Sometimes Chair, sometimes Co-Chair of the EMA Education Committee, Lee wrote a series of little papers called “Bringing history Alive in the Classroom,” on medieval, Renaissance, and early American music. Another two papers concerned holidays—one on Halloween, the second on the winter solstice. “I thought if teachers could take early music and connect it with a holiday, they would have more use for it,” she explained. Lee also contributed to an extensive collection of Early Music Education Resources with Bibliography and Discography, covering medieval, Renaissance, baroque, and early American history and music.

In 1994, Lee conceived and organized the SFEMS Music Discovery Workshop, a week-long, early-music, summer day camp for children, based on the whole body/whole person approach she developed through her work at Walden School, 30 years earlier. Students learned not only the music of the Renaissance and Middle Ages, with opportunities to sing and study recorder, harpsichord, and early stringed instruments; they were immersed in the culture of the period through everything from making costumes and putting on an original play, to playing period games and enjoying historically informed snacks! Initially open to children ages 8–13, the highly successful workshop, now in its 23rd year, has expanded to include a Youth Collegium for more advanced students. Today, the combined programs serve children ages 7–17.

Lee stepped down as MDW Director in 1999 but remained actively involved in Bay Area early music through the end of her life. She continued her work in music education and outreach for several years with her longtime collaborator Ralph Prince and others, doing programs of medieval and Renaissance music in the Berkeley middle schools with their early music demonstration group, His Majesty’s Musicians. She also remained active in the Pacifica Chapter of the Viola da Gamba Society, and (another SFEMS Affiliate group she helped found), the semi-annual Singers’ Retreat, whose 30th anniversary she helped celebrate this past spring.

Lee’s story is a testament to what has built the early music community, especially in the Bay Area, but also as a national and international movement. It shows what just one dedicated amateur—in the most noble sense of that word—can accomplish on the principle that if no one else will do what needs to be done, do it yourself. To paraphrase a statement she and Judith Davidoff drafted for the Education Committee of EMA a quarter century ago, “Early music is a living link to history. Sing it, dance to it, chant it, and you participate in the social ritual of the period—and you never forget it.”