One of the main themes of the upcoming Berkeley Festival is reexamining the nature and meaning of “early music.” Some of the most fascinating happenings the Festival will be presentations of music from the extremes of the historical spectrum. Much attention already has been devoted to the application of historical performance practices to music of the Classical and Romantic periods.

One of the main themes of the upcoming Berkeley Festival is reexamining the nature and meaning of “early music.” Some of the most fascinating happenings the Festival will be presentations of music from the extremes of the historical spectrum. Much attention already has been devoted to the application of historical performance practices to music of the Classical and Romantic periods.

At the opposite end of the spectrum, there will be music of great beauty and historical interest in the two performances by the legendary Sequentia and Benjamin Bagby, making their BFX debuts. Bagby has been engaged in a decades-long project to reconstruct songs from far deeper in our past than what we commonly think of as “medieval music.” This is music centuries older than the Ars antiqua, older than Hildegard; moreover, it evokes traditions of Western culture that are far still more ancient, both the mythology and ethnohistory of the ancient Mediterranean and its counterpart in German and Norse mythology. The songs on their two programs have not been heard in over a thousand years. Their story, and the story of how they were reconstructed, is recounted here in excerpts from the notes to the two programs, by Sam Barrett and Benjamin Bagby.

* * * * *

When we think of medieval monks and their musical lives, the first thing to come to mind is Gregorian chant, the solemn and ritual song which accompanied the monk’s liturgical day, week, season and year. But a closer look at medieval religious manuscripts from the 9th to 12th centuries shows that many monks and clerics were singing other songs as well, with texts which were sometimes anything but Christian. The monastic and cathedral schools of medieval Europe were great centers of learning and focal points of intellectual life. For all monks and clerics, who were native speakers of European vernacular languages (each with their own pagan roots), it was essential to become bilingual—to speak, think, perhaps even to read and write in Latin, the language of their faith, the liturgy, the sciences, philosophy and literature. And this crucial link to Latin could best be enhanced by studying ‘ancient’ texts which had survived: Roman authors, poets, dramatists, teachers, philosophers and historians whose works were studied and memorized, and many of these were also sung. Taken together with occasional Germanic pagan texts, there were songs of the old gods (Woden, Zeus, Jupiter, Bacchus), of men and heroes (Hercules, Orpheus, Boethius, Caesar) and of powerful female figures and goddesses (Valkyries, Fortuna, Philosophia, Cleopatra, Dido, Venus, the wild Ciconians). The survival of these songs, sometimes very fragmentary, provides us with a rich treasure-house of European vocal art, and witnesses to a vibrant culture where the Christian monk gave voice to his pagan ancestors, passing on stories and ideas which resonate to this day.

From the pagan North, many pre-Christian texts have survived, and even in monastic manuscripts we find tantalizing fragments which sometimes mention the old gods. In the form of charms and incantations, they show us an essentially Christian world in which the old beliefs have hung on as folk custom, easily mixing Woden with Christ. As a result, these manuscripts bear witness to a cohabitation typical for recently-converted peoples. The texts, written in Old High German and Old English and found in Christian manuscripts, give us a glimpse into the mysterious northern world of Christianized pagans in the 9th and 10th centuries.

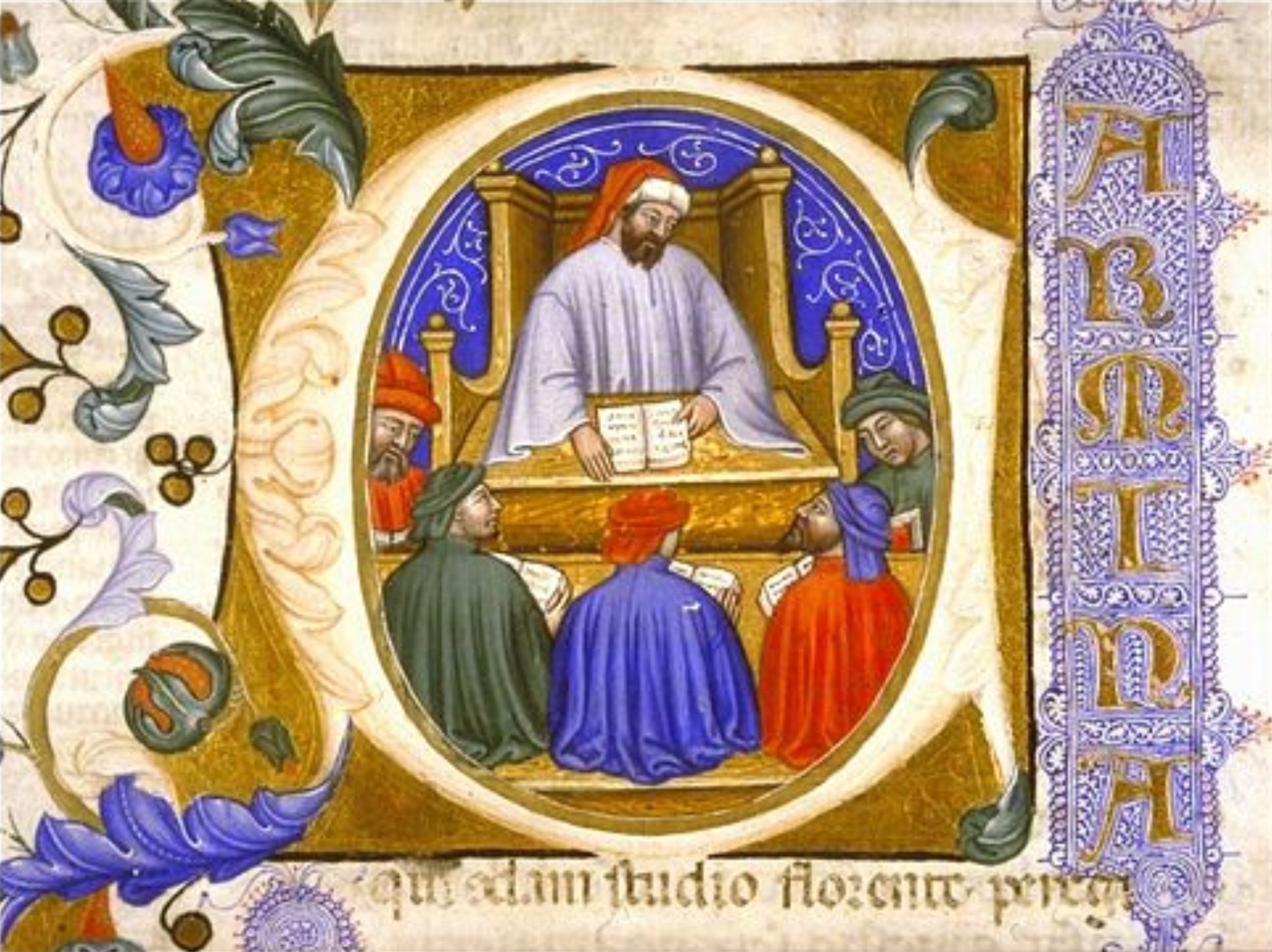

In the gallery of powerful female deities inhabiting the medieval Christian mind, few can rival the fickle force of Fortune, with her ever-changing wheel, or the gravitas of Philosophy, the wise, patient and consoling teacher in times of need. Medieval Christian singers could effortlessly transition between singing about salvation and divine intervention, to singing of Fortune’s unpredictable power over human destiny. A major medieval song collection such as the Carmina Burana (ca. 1235) reveals an almost obsessive fascination with Fortuna. From that collection, Sequentia will perform one of the most famous songs attesting to her power, O varium Fortune lubricum, a song probably created among clerical intellectuals in late 12th-century Paris.

Both of Sequentia’s programs include selections from the Consolation of Philosophy of Boethius (d. ca. 526), and one concert will be devoted entirely to this collection. The musical settings are from the Cambridge Songs (Canterbury, early 11th century). A Roman nobleman and scholar, Boethius (ca. 480–526) had been falsely accused of treason against the Empire and despairs in prison, awaiting execution. As he laments his fate, a mysterious woman appears in his cell: it is Philosophy herself. A long dialogue ensues, punctuated by songs (metra), as she reminds him of the clarity of mind she can impart, and he is cured of his despair. Boethius wrote this story as The Consolation of Philosophy, and it went on to become one of the most important books of the European Middle Ages. In monasteries and cathedral schools of the 9th-12th centuries, the many songs from this book were set to music and sung, but their melodies remained largely lost to us until the groundbreaking work of the musicologist Sam Barrett (Cambridge University), who collaborated with Sequentia on this project, that the songs of Boethius might be heard again.

Evidence that the poems of the Consolation were sung in the early Middle Ages survives in the form of musical notation added to over thirty extant manuscripts dating from the ninth through to the beginning of the twelfth century. The signs used for the notation, known as neumes, record the outline of the melodies, prompting the singer to recall precise pitches from memory. Without access to the lost oral tradition, the task of reconstructing the melodies for the Consolation had seemed impossible.

Research conducted at Cambridge made a breakthrough by identifying song models that lie behind the neumatic notations. It has been shown that medieval musicians associated certain metres used in the Consolation of Philosophy with contemporaneous song styles and then applied characteristic melodic patterns from these repertories to Boethius’ poetry. Scholarly detective work enabled much melodic information to be recovered about individual songs, but the final leap into sound required a second step. Collaboration with the musicians of Sequentia enabled practical experimentation and the opportunity to draw on a working knowledge of early medieval song repertories derived from decades of reconstruction, oral memorization and performance. Proceeding through dialogue, it proved possible to arrive at realizations informed by both scholarly insight and practical experience.

Most of these performances take as their starting point a fragment from the Cambridge Songs, a repertory of over eighty songs thought to have been compiled in part at the Rhineland at the court of the Holy Roman Emperor Henry III (1017–1056). A missing leaf from a copy of the collection made at St Augustine’s Canterbury in the mid eleventh century was rediscovered in the early 1980s. This fragment, now reunited with the original manuscript in the University Library at Cambridge, transmits the opening lines of poems from the Consolation of Philosophy in series. Neumes were added to six of the seven poems from the first book, the most dramatic portion of the text, in which Boethius laments his fallen condition (Carmina qui quondam), is visited and chastised by Philosophy (Heu quam praecipiti) and undergoes an internal transformation that begins the process of returning to his true self (Tunc me discussa).

The recovered Cambridge Song leaf is of vital importance since its neumes can be placed alongside two coeval notated manuscripts from eleventh-century Canterbury. The resulting critical mass of information exceptionally allows informed reconstruction of a body of songs linked to a single center. Beyond this, the inclusion of Boethian songs within a substantial song collection associated with episcopal and royal courts, whose texts tell of singing to the harp and of performance at the ‘palaces of kings’, provides evidence that these songs were sung and played by highly trained musicians to members of an educated and social elite within what was already a sophisticated European song culture. There are plenty of other indications that these songs were sung in the cathedral schools and monasteries renowned for their learning as part of a clerical culture that extended from boys through to highest ranking prelates.

* * * * *

Sequentia will appear in two performances at the Berkeley Festival and Exhibition: Thursday, June 7, at 10:00 p.m., they will present “Boethius, Songs of Consolation,” and at 4:00 p.m. on Saturday, June 9, they will present “Lost Songs: Monks Singing Pagans.” For tickets to these and all the other amazing shows at BFX2018, visit Berkeley Festival.

For more information on the Lost Songs Project, visit http://sequentia.org/projects/lost_songs.html