For February’s concert in our 2014–15 series, SFEMS is proud to present Dark Horse Consort, comprised of sackbut players Greg Ingles, Erik Schmalz and Mack Ramsey, together with cornettists Kiri Tollaksen and Nathaniel Cox (Cox will double on theorbo) and Peter Sykes on harpsichord and organ. Named after the bronze horse statues at Venice’s St. Mark’s Basilica, the 4-year-old group recreates the glorious sounds of an early 17th-century brass ensemble. Guest vocalists Jolle Greenleaf and Molly Quinn join Dark Horse in their Bay Area debuts. Their concert, the weekend of February 20–22, will feature works by the famous trilogy of Heinrich Schütz, Johann Hermann Schein, and Samuel Scheidt, as well as by a half-dozen composers they influenced: Dietrich Buxtehude, Andreas Hammerschmidt, Johann Rosenmüller, Thomas Selle, Johann Vierdanck, and Matthaius Weckmann.

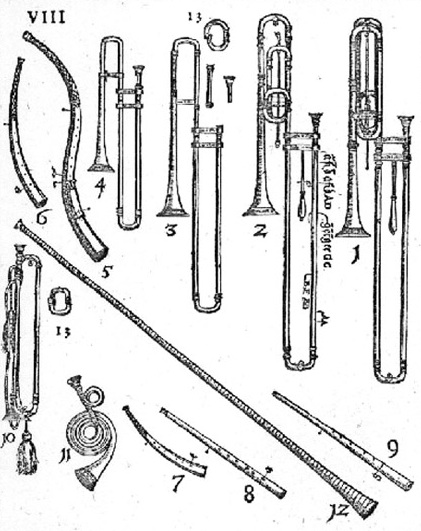

Brass ensembles of the 16th and 17th centuries had both a distinct sound and different function from their latter day descendants in military and marching bands. Softer and more mellow than their modern equivalents, the sackbut (an early trombone) and cornett (a hybrid instrument with wooden body and finger holes like a flute but a cup mouthpiece like a horn) were noted for having sonorities closer to the human voice than any other instruments. While they were called upon to play toccatas, canzonas and other purely instrumental music, perhaps their most important function was to blend with singers and accompany them, especially in the performance of sacred music. A consort of cornetts and sackbuts can achieve a purity of tone and perfection in tuning that must be heard to be believed. These instruments’ ability to match vocal timbres and articulation create a richer, more vibrant effect than voices alone ever could achieve, while actually helping clarify the sacred texts, which in mixed vocal-brass ensembles would be sung by only one or two voices.

The vocal nature and virtues of brass instruments were well understood and appreciated by musicians and critics of the period. In his memorandum to the Cabildo of Seville’s Cathedral (1586) Francisco Guerrero wrote that if a tenor or baritone singer was absent, he might be replaced by a sackbut; likewise, a cornett could substitute for a missing soprano. In his Harmonie Universelle (1636/7), music theorist Marin Mersenne compared the sound of the cornett to a ray of sunlight penetrating the darkness and wrote that the sackbut should not try to imitate the sound of the trumpet “but rather assimilate itself to the sweetness of the human voice, lest it should emit a warlike rather than a peaceful sound.” In an era when the human voice was considered the most perfect of all instruments, such comparisons represented the highest possible praise.

This is a concert that has begged to be done for a long time. Ironically, despite the groundswell of interest in 17th-c. composers that has swept the early music community in the past two decades, a program such as this—pure polyphony mixing voices and brass—to my knowledge has not been performed here before. The music on Dark Horse’s program, focusing on the period between the 1590s and 1650s in Germany, offers a perfect repertory to demonstrate the beauty and effectiveness of this combination. Dark Horse’s Greg Ingles provides the following, extended note on the concept behind their concert and the music they will perform.

* * *

“Consort” – A small ensemble of voices and/or instruments playing music composed before 1700.

“Broken Consort” – A term generally taken to mean a consort of instruments of different kinds.

When one refers to the Renaissance terms Consort or Consort Music, the image that generally comes to mind is a cohesive ensemble of unified instrumentation. Though the popular consorts of the Renaissance were made up of groups of amateurs playing violas da gamba or professionals intoning violins, recorders, or loud instruments, this definition can also refer to an ensemble of singers.

The early brass consort comprised of cornetti and sackbuts (trombones) is intrinsically a broken consort. There is no evidence of a soprano member of the trombone family and though there a number of original tenor cornetti (lysarden) and a few surviving alto cornetti, there is only 1 original bass cornetto extant. Though never truly homogeneous like a complete consort of viols, violins or recorders, the broken brass consort of cornetti and sackbuts can create a satisfying blend and is quite pleasing to the ear. The brilliance and clarity of the cornetti bring out the top melodic lines, newly important at the turn of the 17th century, while the darker and softer sackbuts produce a supportive bed of sound on the lower lines. As lip-buzzed aerophones, both instruments produce their sound by the same means, by vibrating the lips into a cup shaped mouthpiece, which is amplified by the corpus of the instrument. This results in a certain unity of tone color when combined. Indeed, much of the technique needed to change the sound of the instruments happens even before the mouthpiece. Tone production begins inside the oral cavity, much like a singer. Brass instrumentalists can try to exactly match vocal text, both consonants and vowels, through a variety of means. Instrumental treatises from the early 17th century describe a range of articulations, from smooth through crisp, using both the tip of the tongue (re, le, de, te) and also an explosive technique from the back of the throat (che), much like the English k sound. These expressions are strung together to have series of strong and weak syllables (te-re-le-re, de-re-le-re, te-che-te-che), emulating the undulations of human speech.

The distinct vowel of each texted syllable changes the timbre of the tone on which it is sung. Brass players, both cornetti and sackbuts, can vary their “vowels” by changing the placement of their tongue inside the mouth. By overemphasizing the high-tongued placement of “ti” (sounding like “tea”) a smaller resonating cavity is produced, which makes a brighter, compact and more piercing tone. By lowering the jaw down and forward with a “toh” articulation (sounding like “toe”), more space is made inside the mouth, producing a darker and rounder tone color. Both of these vowels settings, and all of the slight gradations between them, are used with the many kinds of consonant articulations to create myriad possibilities of color and shading to every note. All of this description is meant to show that brass instrumentalists both make and change their specific tone colors in a somewhat similar fashion to vocalists, resulting in a purer blend when sounded together.

With this premise in mind, I attempt to show that a consort of cornetti and sackbuts with singers, though all of varying individual tone colors, have enough in common to constitute a complete consort that can at times sound unbroken. Roger North, a 17th-century English biographer wrote, “Nothing comes so near or rather imitates so much an excellent voice as a cornett pipe.” If performed with these values in mind, the lines between the various tone colors are blurred in such a way that the listener is hard pressed to determine which part is being played and which sung.

We begin the program with a resounding Intrada by Alessandro Orologio, demonstrating an example of the early brass consort sound. Like the majority of other instrumental music of the time, Orologio’s intradas were composed for four or five separate parts, SATB or SSATB, matching the model for analogous vocal repertoire. This simple introductory piece is tightly woven in the Germanic fashion, with the top two lines trading melodic motives and ornamentation in a conversational manner.

(photo: Andrew Strawcutter)

One must never forget that the vocal consort was the dominant music ensemble in the Renaissance and early baroque periods. Much of the music that instrumental ensembles played was actually texted vocal music. Herman Schein’s Opella Nova I & II were collections of vocal motets with various settings, some for voices alone, others including separate instrumental parts. Both the “Ich ruf zu dir” and “Aus tiefer Not” from Opella Nova II are set for two soprani with basso continuo, each calling for keyboard and unspecified instrumental bass in the continuo, here realized with a bass sackbut. The soprano parts make great use of imitation, at times responding to one another in a flourish of ornamentation, then coming together to iterate important phrases of the text.

There are many pieces from the early 17th century where the divide between voice and instrument dissolves, not because the instrumentalists modify their technique to match the singer, but because the singer’s melody or text portray the sound of a certain instrument. Heinrich Schütz’s “Es steh Gott auf” begins with the obbligato instruments playing a tune meant to recall a trumpet fanfare. When the voices enter they take up that ecstatic call and when their voices can no longer be contained, they burst forth in a flurry of melismatic pyrotechnics. Conversations between the voices (and between the voices and instruments) ensue, culminating in the rare union of an Italianate ciaccona set to German sacred text.

The text of Psalm 98, “Singet dem Herrn ein neues Lied,” perfectly lends itself to the craft of voices mimicking instruments, and almost every Germanic composer from Schütz to Bach tried his hand at this process with this specific text. The text instructs the listener (and the singer) to:

Praise the Lord with harps and melodic sound! With trumpets and trombones Make a joyful noise before the Lord, the king.

The setting of this Psalm and its analogous text in Psalm 150 gives the composer a chance to imitate harps and strings, trumpets and trombones, flutes, drums, psalterys and cymbals. The way this is achieved depends on the imaginative setting of each composer, but the intent is clear; that the meaning of the work should be understood not just through the text itself, but also through the way the music portrays the meaning of the text.

Instruction about orchestration can be found on the cover or in the dedication of many sets of part books. Printed instructions like per voci et alcuni strumenti (for voices and some instruments) and per ogni sorti strumenti (for various sorts of instruments) indicate that, when a composer penned a collection of vocal music, the parts could all be sung, but that it would be equally valid to play the parts on various instruments or a mixture of instruments and voices. The Deliciarum Juvenilium by Thomas Selle gives a clear set of such instructions for performance. The ten pieces in the collection each have one instrumental and one vocal part, but the interchange of the melodies and the similarity of the ranges and usage of both “voices” clearly indicates that both parts could have text and be performed as a vocal duet. Both melodic parts are written in treble clef, and Selle suggests that the instrumental line be played on a violin, mute cornetto or a recorder. He also recommends playing the pieces with only two instruments or taking both parts down an octave, with the vocal part being sung by a tenor and using a trombone or bowed bass on the instrumental line. For variety, we’ve arranged the “Ade, du edles Mundlein roth” and the “Frisch auff mein Herz” from this collection to feature different orchestrations throughout the works.

In a similar manner to the works by Selle, we’ve chosen to set Heinrich Schütz’s vocal duet “Erhöre mich, wenn ich dich rufe” with a cornetto replacing one of the vocal lines. This type of setting shows the cornetto’s ability to mimic the soprano’s textual nuance, but, as with all polyphonic music set with one sung line accompanied by instruments, it also has the added advantage of allowing the text to be heard clearly and distinctly.

Samuel Scheidt’s simple setting of the vocal concerto “Komm Heiliger Geist” for two sopranos and two trombones utilizes its small forces in inventive ways, using the two trombones or two sopranos alone, paired in two equal duets of one voice and one instrument or by sounding all together. The instrumental parts of these works were often called upon to quickly change roles from playing pure accompaniment, to playing imitative lines that “commented” on the text, to also being an equal “voice” that expanded the vocal consort and helped to declaim the text. Similarly, the three unspecified instrumental lines in Hermann Schein’s tightly composed and dense “Christ, unser Herr” sound a consistently undulating underlying obbligato for the voices. The imitative layout of the two vocal lines acts almost as an instructional guide to 17th-century passaggi, starting with a single line sung simply in one voice, only to be repeated in the second voice with incredibly florid, exciting and uplifting ornamentation.

Andreas Hammerschmidt’s “Herr unser Herrscher” utilizes a five-part instrumental obbligato most creatively while accompanying a single voice. The instrumental force is used as a narrative device whose madrigalian imagery and word painting can be seen in the text:

Sheep and oxen all together, with them the wild animals, the birds of the sky and the fish in the sea and whatever follows its paths in the sea.

Late in the work, when the mammals are mentioned as being “all together,” the instruments play a compact and closely harmonized phrase as one. When Hammerschmidt sets the instruments to describe the “birds of the sky” the melodic lines go high in the instrumental tessitura and have fluttery passaggi. Conversely, the fish in the sea are set in a low register, its effect as calm and soothing as a cool stream. These madrigalisms were vital in helping the average parishioner better visualize the sacred text of the vocal concerto and bring the listener that much closer to God.

The role of the accompanying instruments sometimes mutated within a single work. Rosenmüller’s “Lieber Herre Gott” for soprano and three trombones begins with the instruments in an obbligato, commentary role but quickly morphs into using the alto, tenor and bass trombones as lower voices in a “vocal” quartet, uniting with the soprano as an integrated choir. Throughout the rest of the piece, Rosenmüller fluctuates between using the trombones as obbligato instruments and choral voices.

It is well known that instrumental music of the late Renaissance and early baroque borrowed heavily from vocal repertoire. The traditional folksong “My Lord Willoughby’s Welcome Home” is about a battle in the Low Countries in the 1590s and was so popular it was set by John Dowland as a lute duet, and was later heard in Germany as a canzona under the title “O Nachbar Roland,” set as an instrumental quintet by Samuel Scheidt. Ever the innovative organist, Scheidt sets the piece in increasingly complex variations culminating in a final explosive setting in double time. Similarly, Johann Vierdanck’s sonata, titled “Als ich einmal Lust bekam,” was based on the folksong of the same name by Gabriel Voigtländer. Vierdanck breaks apart the simple melody into motives and reworks them in layers throughout the piece, much like the development section of a Romantic era sonata. Most striking and unusual, however, is the setting of the original melody monophonically, with all of the instruments playing the simple melody at the same time. After hearing dense, motivic polyphony, this simple iteration can be jarring to the ear, but Vierdanck uses this technique quite effectively to remind us of the original melody.

Many works for keyboard had their origins in vocal repertoire similar to the instrumental consort music of the time. Matthias Weckmann’s simple set of variations on the secular tune “Lucidor einss hutt der Schaf” is rather straightforward in its delivery of the melody. The opening A section is repeated with simple ornamentation, which is then followed by a setting of the B section, also ornamented in the repeat. This entire A-A’-B-B’ is repeated, newly set with increasingly complex rhythmic activity, bringing it further and further away from its vocal beginnings and more into the realm of purely instrumental music.

Buxtehude’s organ prelude to the choral tune “Ich ruf zu dir, Herr Jesu Christ” is a tour de force of ornamentation and inventiveness. Like most works of this genre by Buxtehude, and later by J.S. Bach, the original chorale tune is heard intact in one of the “vocal” lines while the other voices provide polyphony to accentuate the melody, but never dominate it.

The supremacy of voices and vocal repertoire in the Renaissance and early baroque cannot be denied, but the inherently broken consort of voices, cornetts, and sackbuts can result in a pleasing and satisfying unification of timbre and articulation. This program is meant to show not just the possible blend of the various components with one another but also the ingenuity and innovation of the composers in merging the vocal and instrumental worlds. It is precisely because of the vastly successful integration of these forces that we have such a wealth of repertoire written for this combination.

Performances will take place at 8:00 p.m., Friday, February 20, at First Lutheran Church, 600 Homer Street at Webster, in Palo Alto; 7:30 p.m., Saturday, February 21, at St. John’s Presbyterian Church, 2727 College Avenue at Garber, in Berkeley; and 4:00 p.m., Sunday, February 22, at St. Mark’s Lutheran Church, 1111 O’Farrell Street at Gough, in San Francisco. Tickets are available online Tickets are available online or through the SFEMS box office at 510-528-1725.