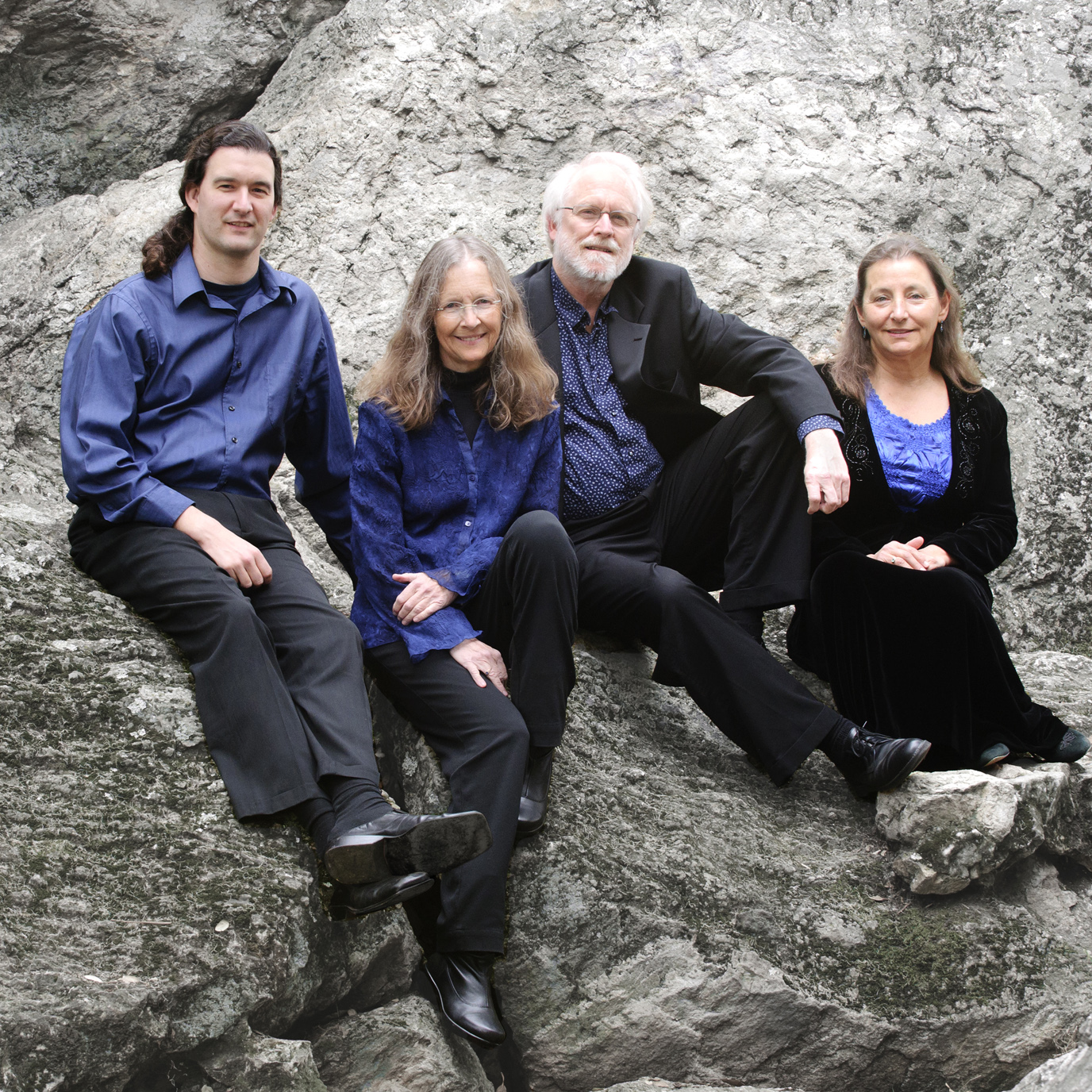

The weekend of November 17, New Esterházy Quartet (Kati Kyme and Lisa Weiss, violin; Anthony Martin, viola; and William Skeen, cello) will recreate a lively party in Vienna in 1784, when Mozart and Haydn played chamber music together with violin virtuoso Karl Ditters and composer Johann Vanhal at the house of their friend Stephen Storace. The program features one string quartet by each of these composers.

Anthony Martin—who will play the part Mozart played—tells the tale and previews the upcoming show.

* * *

The story that is the basis of our upcoming program from Vienna dates from 40 years after the fact, just like Cambini’s tale that created The Tuscan Quartet we focused our September concerts on.

The memoirs of the Irish tenor Michael Kelly appeared in 1826, the year of his death. In them he details his life as an international star of the stage, a composer, a singer, an actor, a theatre manager, a skilled raconteur, a friend of both royalty and lowlife. And of Mozart.

Kelly, known in Italy as Ochelli, at age 24 sang the roles of both Don Basilio and Don Curzio in the Vienna premiere of Le Nozze di Figaro. He gives interesting descriptions of Mozart in rehearsal, and tells of his never being able to best Mozart at billiards.

Two years before Figaro, Kelly was involved in the premiere of an opera by Giovanni Paisiello, with a libretto by Giovanni Battista Casti. During the preparations for this opera there was a little party given by Kelly’s good friend Stephen Storace, an English composer and gad-about, whose sister Nancy was to sing as Mozart’s first Susanna and in Haydn’s London concerts in the 1790s. Kelly’s description of this 1784 party is the basis for our concert today:

“…in the interim Storace gave a quartett party to his friends. The players were tolerable, not one of them excelled on the instrument he played; but there was a little science among them, which I dare say will be acknowledged when I name them:

The First Violin……………………Haydn.

” Second Violin…………………Baron Dittersdorf.

” Violoncello…………………….Vanhall.

” Tenor……………………………Mozart.

The poet Casti and Paesiello formed part of the audience. I was there, and a greater treat or a more remarkable one cannot be imagined.

On the particular evening to which I am now specially referring, after the musical feast was over, we sat down to an excellent supper, and became joyous and lively in the extreme.”

We hope it is fair to assume that the four composer/performers, with no little science among them, brought their latest compositions to the party, with appropriate pride and modesty. We can easily imagine how it got started:

“Whose music shall we hear first? How about you, Jan?”

“Oh, no, I couldn’t imagine it, what have you brought, Karl?”

“Don’t be silly, I bet that Joe has something new for us.”

“Wait, what? I could not stand comparison with Wolf!”

And so on, until finally one of them gave in, put some parts on the stands, and off they went. Surely they took all the repeats marked by the composer, the first time through a section serving as rehearsal, the second as performance. And it takes very little to imagine how these jovial geniuses, after their musical feast, became “joyous and lively in the extreme.”

On the other hand, as the saying goes, there are warts. Kelly’s book was compiled by the notorious Theodore Hook, in-and-out of English debtor’s prisons, about whose editorial efforts even Kelly complained. Two unreliables reporting events at a distance of over 40 years could lead to some misgivings about details, even if the broad outlines are accepted. For instance, how could Haydn, who was merely a capable violinist, have played first to Karl Ditters (Baron von Dittersdorf), a celebrated virtuoso and professional concertmaster? And this is the only reference I am aware of to Jan Baptist Vanhal, composer, violinist, pianist, and singer, as a cellist. We do know from other sources that Haydn and Mozart enjoyed playing chamber music together, and that their genuine friendship was based on mutual appreciation and admiration. Ditters, who was a drinking buddy of Haydn, also admired Mozart, although he complained more than once that Mozart’s compositions were too dense to be fully comprehended and therefore would never be popular.

On the other hand, as the saying goes, there are warts. Kelly’s book was compiled by the notorious Theodore Hook, in-and-out of English debtor’s prisons, about whose editorial efforts even Kelly complained. Two unreliables reporting events at a distance of over 40 years could lead to some misgivings about details, even if the broad outlines are accepted. For instance, how could Haydn, who was merely a capable violinist, have played first to Karl Ditters (Baron von Dittersdorf), a celebrated virtuoso and professional concertmaster? And this is the only reference I am aware of to Jan Baptist Vanhal, composer, violinist, pianist, and singer, as a cellist. We do know from other sources that Haydn and Mozart enjoyed playing chamber music together, and that their genuine friendship was based on mutual appreciation and admiration. Ditters, who was a drinking buddy of Haydn, also admired Mozart, although he complained more than once that Mozart’s compositions were too dense to be fully comprehended and therefore would never be popular.

The four works by these composers we have selected are nearly contemporaneous with Storace’s Viennese party of 1784. The six quartets of Haydn’s Op. 33 were written in 1781 and first printed the following year. The first of Mozart’s set of six dedicated to Haydn was written at the end of 1782, Ditters’ set of six did not appear in print until 1789, and Vanhal’s last six quartets were written in the mid-1780s. Vanhal had been a prolific quartet writer, with as many as a hundred in print and in manuscript to be found in European and American libraries. His withdrawal from quartet composition conceivably could have been prompted by his awareness, in that fast company at Storace’s, of the depth of the up-and-coming competition. But let us leave all quibbling and speculation to the side and enjoy the musical feast of this joyous and lively party!

* * *

New Esterházy Quartet performs 8:00 p.m., Friday, November 17, on the Hillside Club Concert Series in Berkeley (Hillside Club, 2286 Cedar Street (at Spruce), Berkeley); 4:00 p.m., Saturday, at St. Mark’s Lutheran Church, 1111 O’Farrell Street, San Francisco; and 4:00 p.m., Sunday, at All Saints’ Episcopal Church, 555 Waverley Street (at Hamilton), Palo Alto, Please note that the ticket price for the Friday concert at Hillside Club are $25 and are available at the door. The Saturday and Sunday performances are self produced by NEQ. Tickets $30 (discounts for SFEMS members, seniors, and students) and are available by phone at 415-520-0611 or through the NEQ website, www.newesterhazy.org